In 2014 I surprised myself by writing a book. This is by no means the first book I have written, so perhaps some of you will be surprised that I was surprised, but I had just finished the monster-sized project of writing and launching my new on-line course. I wasn’t expecting to take on another big project quite so soon on the heels of that endeavor.

But books are funny things. You don’t so much write them as they write themselves. When a book wants to pop out, if I am anywhere near a computer or a pad of paper with a pen in my hand, that’s what is going to happen.

Once the book was written, there remained the question of what to do with it. The normal answer is you publish it as a hold-in-your-hand actual book, but somehow that didn’t seem the right answer for this particular project. I sat with it for a year while I considered what I wanted to do. In the end I have decided that what I wanted was to share it here.

I’m going to publish my book in this blog, section by section. I hope you enjoy it. It was written first and foremost for my horses, perhaps you could even say by my horses. It is a gift from them to you.

Happy New Year 2016

Alexandra Kurland

Before I begin the book, let me share with you why it was written.

2014 was a dreadful year for me. It’s astounding how fast your world can be turned upside down and inside out. I arrived at the barn on Feb 10, 2014, as usual. Robin and Peregrine greeted me at the paddock gate, as usual. Robin bowed, stretching both front feet out in front of him and crossing one leg over the other – again as usual.

The bow is part of a favorite morning game. It’s his cue to me to open my car door. I always feel like a jack-in-the-box popping out of my car on his signal. I opened my car door, as usual, and gave both Peregrine and Robin good-morning-greeting treats from my pocket.

I got my backpack out of the car and headed up to the barn. Fengur and Sindri, our two Icelandics, were there to greet me as I reached their section of the barnyard. Robin and Peregrine were already inside the barn, waiting for me in the aisle.

I went through my morning routine. I fixed Peregrine’s mash, passed out hay for everyone, put Robin into his stall, closed the back gate to his “sun room” so he couldn’t help himself to Peregrine’s breakfast, gave Peregrine his mash and had just started on Sindri’s stall when I heard Robin banging against his stall wall. I love the open design of the stalls in the new barn. I could look down the line of stalls and see all the horses. Robin looked as though he was trying to stretch out in a bow but there wasn’t quite enough room.

“That’s interesting,” I thought. “He’s transferring the bow up to the barn.” I wanted to capture the moment, but I was too far away. I continued on with Sindri’s stall, but I was listening now, on the alert for a repeat performance. Sure enough Robin bowed again. This time I was prepared. I rushed over, but not in time to capture the bow. Robin had gone outside into the small run directly outside his stall. A quick glance told me something was wrong.

It took no more than an instant to switch from the playfulness of clicker training to the dread of a colic alert. This wasn’t his normal bow inviting me to come play. The stretch that I was seeing was something entirely different. In the space of no time at all Robin’s gut had seized up into full colic pain.

Thank goodness for cell phones. I never thought I would hear myself say that, but it meant I didn’t have to leave Robin to call the vet. I got him out of the stall and into the arena. Less than an hour later the vet was there, not my usual vet, but one of the younger members of the practice.

Robin blew through all the pain meds she gave him. Suddenly we were talking about surgery. “If you think it’s an option, you should ship him now.”

I couldn’t believe I was hearing those words, not for Robin. He was my healthy horse. He was never sick. He’d never even had a lameness exam. He’d certainly never coliced, and he had none of the common risk factors for colic. He wasn’t confined to a stall. Yes, the pastures were closed for the winter, but he and Peregrine had free run through the barn, the indoor arena, and their outside paddock area. He drank a lot. His weight was good. He had none of the signs of metabolic disease that has become so common in older horses. Given all the horses I know, Robin would be the last one I would expect to colic – and yet here we were talking about surgery.

I knew from clients who had gone through this experience that colic surgery was survivable, but you needed to ship early. The longer you waited, the lower the chances were for a good outcome.

But surgery. For Robin.

He was my healthy horse. I didn’t want him to become an invalid. That wasn’t the kind of life he would enjoy.

And then there was his shadow, Peregrine. Peregrine is my elderly thoroughbred. In the last couple of years he had become completely dependent upon Robin for security. I’m not sure Robin appreciated having a constant shadow, but Peregrine didn’t really give him any choice. In 2011 when I moved the horses to their new home, Peregrine coped with the change by attaching himself completely to Robin. Fierce Robin, who had never really buddied up with anyone, slowly discovered that he liked having someone to hang out with and take naps with. They had become a pair, sharing everything including training time with me.

But now Robin was in the arena, filled with drugs that didn’t even dull his distress. Peregrine was hovering nearby. He clearly knew something was terribly wrong. What was I to do? If I kept Robin here, I was going to lose him. And then what would Peregrine do? The unthinkable was happening. It was never supposed to be this way. Robin was so much younger than Peregrine and he had ALWAYS been so healthy. How could he be colicing?

If you’re going to ship them, ship them sooner rather than later.

I knew this truth. I knew I had to make a decision, but how was I going to trailer Robin anywhere? This was February. The only available trailer on the property was snowed in. And how could I leave Peregrine? I wouldn’t be able to go with Robin.

I started making phone calls. It took another hour to get everything organized, to get a driver for the trailer, to get the trailer dug out, the truck hitched up.

If you’re going to ship them, ship them sooner rather than later. The day had begun so normally. And now just a few hours later, I was leading Robin out to the trailer and shipping him off without me.

Bob Viviano, one of my long term clients and good friends, drove Robin for me. We are lucky in this area to have an excellent hospital within an hour’s drive. We gave Peregrine a sedative which bought me the time I needed to get Robin on the trailer. He loaded without hesitation and I sent Bob off. It was then a little after noon.

Half way to the hospital the snow started. Bob drove through white out conditions from a storm that was moving in from the coast. If I had known there was snow to our south, I would never have risked his safety to drive Robin. Instead of an hour’s drive, it took him closer to two to reach the hospital.

I was waiting in the barn for news. At two thirty I heard that Robin had arrived safely and was being examined by the vets. Bob was heading back.

Peregrine had woken up by this time and had begun to pace. I closed the outer stall doors to try to keep things a little warmer for him. There was nothing I could do to ease his distress except to give him back Robin. I had to hope that was going to be possible.

The news from the clinic didn’t sound good. They were recommending surgery. Was that an option?

I talked to the surgeon about what I wanted for Robin. If it meant he would be left in chronic pain with a disabled life, then no, I didn’t want to operate.

She thought there was still a good chance for him. How can you say no? I said yes to the surgery.

I waited. The hours passed. There was another horse in surgery ahead of Robin. As soon as that horse was in recovery, Robin’s operation would begin.

At six I got another call. Robin was being prepped for surgery.

Peregrine continued to pace. He walked through the night, unable to settle. I stayed with him, but it was Robin he needed.

At midnight I got the call, the call we all dread. I had another decision to make. They had found a twist. A full twist with dead small intestine.

I had learned from my clients that if you are going to ship them, ship them sooner rather than later. I had also learned that cutting out intestine was the deal breaker. That’s where you stopped.

So he’s a dead horse. That’s what I thought as I heard the news.

But the surgeon thought there was still a chance. The twist put him into the category of worst case scenario, but given that, he was in better shape than many horses who had twists. He still had a good chance. My world had flipped and flipped again. What was she saying? What decision should I make? How could I say no? How could I stop now?

I told her again what I wanted for Robin. I wanted him to live, but not if it meant he would be left in a state of chronic pain. I told her it was okay to continue, and it was also okay to stop.

I wish I could have been there. I don’t know what decision I would have made if I had seen the pain Robin was in. But in the barn with Peregrine continuing to pace, I gave permission to continue.

At 2:30 in the morning the call came. Robin was in recovery.

Peregrine continued to pace. At dawn I opened up the outside stall door and let him out into the barnyard. Peregrine liked to sunbath. I hoped the warmth from the early morning sun would help him to settle. He went out into the snow and rolled. All very normal, and then he got cast.

I never knew it was possible for a horse to get cast in snow, but the conditions were just right for this calamity. The weight of his body packed the snow into ice. It formed a perfect cast along his backside. The ridge line of ice kept him from rolling back onto his side. He was trapped on his back, his feet waving helplessly in the air. After a night of constant walking, he didn’t have the strength left to get up. I could see in his eyes that he was giving up.

I couldn’t get him up by myself. I made frantic phone calls. I put in a call to the vets. They were only ten minutes away. Someone would be there at this hour who could get here fast.

While I waited, I dug away at the frozen snow. I cleared enough to tip Peregrine more onto his side. He struggled, found a bit of purchase, and was on his feet just as the vet arrived.

Disaster averted, but I couldn’t help but think how close I had come to losing both my horses in the space of twenty-four hours.

I stayed with Peregrine throughout the day. I wanted to see Robin, but I knew he was getting the full care he needed. Peregrine needed me more.

By evening he was settled enough that I could leave him in the care of others. I drove down to see Robin.

Robin greeted me with a nicker. I don’t know what I had expected, but not this. He looked so healthy, so very bright. He posed for me. “Oh don’t do that, Robin, you’ll hurt your stitches.”

The surgeon and intern stopped by and stayed for a long time answering questions and just visiting.

I stayed with Robin. His surgery was rapidly emptying my bank balance and putting me deep in debt, but that evening, when he rested his head against me, I knew I had made the right decisions.

I finally had to leave. I slipped out of his stall, but before I could leave, Robin posed – his sure cue to me for attention. The pose was a behavior he had learned when he was two. It had been the cornerstone of his training – helping him to develop the most glorious gaits and also giving him a sure-fire way of engaging me in clicker games.

So soon after surgery he wasn’t allowed anything to eat. I couldn’t give him any treats, but that’s not what he wanted. He wanted me to stay with him. I opened his stall door and went back inside to hug his face – another favorite behavior.

I tried to leave again, again he posed. I laughed. He was turning my leaving into a game. I went in and out a few more times for him, and then I slipped away.

The following afternoon I went down again. The brightness was gone. Robin was crashing. He was in terrible pain. The vets did an ultrasound looking for gut motility, looking for signs of more damage, or worse, more dead intestine or another twist. What they could see encouraged them. There were no obvious signs of further damage.

Over the next couple of days Robin’s temperature shot up. What little manure he passed came out as liquid diarrhea. He was put into an isolation stall. When I visited him, I had to don protective gear – gown, gloves and boots before going into his stall.

My days took on a pattern. I slept at the barn, so I could keep an eye on Peregrine. I made a bed for myself in the tack room by stacking bags of shavings together. In the morning I would wake up early and do the morning chores. Then I would wait for the call that would tell me if Robin had made it through the night.

While I waited, I wrote. I worked on a book. It was originally supposed to be a series of articles for my on-line course, but day by day as I waited for news of Robin, it grew into a book.

Robin continued to fail. To protect his feet from laminitis they kept him wrapped up round the clock in ice boots. He hated the boots. He was in constant colic pain in spite of the pain killers he was on. Every afternoon, all afternoon I stayed with him in his stall. Some days all I could do was lean against the wall and watch as his muscles quivered in spasms with the pain and the fever. Other days he would lie down and sleep with his head resting in my lap. I sat in the deep shavings and kept a vigil, monitoring every little change.

The days passed. The money poured out. While I worried how I was going to afford all of this, I wrote a book about Play. Odd how things evolve.

I knew always Robin might not come home. He was so very sick. The vets suggested that we give him platelets, but they wanted to check with me first. The platelets were $500 a bag. Ah well, I thought, so much for getting the new computer I so very much needed.

A week went by, then another. I watched some horses go home. Others came in, most for colic surgery, most were thoroughbred mares with newborn foals at their side.

I watched the staff give all the horses superb care. Never was there any concern about leaving Robin with them. There was no rough handling, no yelling, no treating any of the horses like livestock. It was careful, caring, gentle handling.

During the second week Robin began to show more interest in eating. At first, he was offered only small handfuls of hay several hours apart. Then he was given a bowl of hay and finally a hay net. At first all this did was make the diarrhea and the pain worse, but then on his second Saturday in hospital he started to look brighter. His temperature finally dropped, and he began to eat more normally. When I arrived in the afternoon, I was greeted by the welcome sight of a full hay net hanging in his stall. The following day he continued to do well, so on the Monday, two weeks to the day of his arrival, he was cleared to go home.

I continued to live in the barn through the winter, huddled near a space heater in the tack room so I could keep an eye on Robin. He was confined to his stall for a couple of weeks, then he was allowed out into his small outside run.

Peregrine helped me watch over him at night. I always knew when Robin was lying down. Peregrine would begin to pace. The tack room is directly opposite Robin’s stall so Peregrine’s pacing would wake me in the middle of the night. I’d slip out to check on Robin. Always he looked comfortable, just resting, but I often had to get him up or Peregrine would continue to fret. After about two weeks, Peregrine relaxed and let Robin – and me – sleep as needed.

Two months on from the surgery, Robin was allowed the freedom of the barn plus the arena, and then another month on from that he was allowed normal turnout.

As he got better, my writing time disappeared, and the book project went on hold. Now that spring was here, there were more pressing outside jobs to do, plus my travel schedule was back in full swing.

In June the nightmare repeated itself – this time with Sindri, Ann Edie’s Icelandic stallion. He went off his feed, and he had a low grade temperature. We had the vet out right away. The diagnosis – anaplasmosis, one of the tick-borne fevers. Apparently, this was hitting our area hard this year, and they were being run ragged getting to all the horses who were showing similar symptoms.

Sindri had had Potomac Horse fever eight years previously. He’d had a bad reaction to the tetracycline, the antibiotic that is used to treat it. His kidneys shut down, and we came very close to losing him. Tetracycline is the drug of choice for anaplasmosis, but given his previous reaction, the vet chose an antibiotic from a different family of drugs.

This was on Saturday. Sindri’s temperature dropped back to normal, and by Sunday he was back to eating and drinking normally.

Monday morning as I was turning him out, I saw a slight misstep as he came out of his stall. Alarm bells started ringing. The vet was out doing a recheck on Robin.

As we were finishing up with Robin, I mentioned that Sindri hadn’t looked right that morning. He’d been a little off, and I was worried about laminitis. We walked out to look at him. Sindri walked up to us. He looked fine. There was no obvious lameness, no heat or pulses in his feet.

The vet left. I busied myself about the barn where I could keep an eye on the horses. When I checked Sindri again a short time later, he could no longer walk. The tinge that I had seen had grown into full blown laminitis.

I called the vet out again. This time there was no mistaking what was happening. The anaplasmosis had tipped him into laminitis. My vet wanted us to keep his feet wrapped in ice boots and to stand him on sand to try to support his feet. There was no way could get a load of sand delivered on such short notice, so Ann’s husband went off instead to Lowes to bring back bags of builders sand.

He brought us bags of ice and fifteen bags of sand. That didn’t even begin to give us the coverage we needed. Three trips later we had enough sand to get Sindri through the night.

The following day, Sindri looked so much better. I thought with relief that we had dodged that bullet. He was going to be all right. But the following day he crashed again. Laminitis is like that. You think you’re making head way, and then cruelly it flares up again with crippling pain. The only good news was the x-rays showed no rotation of the coffin bone.

Sindri was on painkillers and other medications to try to control the inflammation. He seemed to stabilize, but he was still sore. And we had to keep his feet in ice boots round the clock. Every two hours I repacked his boots with ice. I could feel my brain turning to mush as the sleep deprivation set in.

Sindri seemed to stabilize. He was allowed five minutes in the arena. Turning he was very sore, but on a straight away he walked out in big reaching strides. I turned him loose in the arena so he could choose what he wanted to do. What he wanted was to trot up to me as I cleaned manure piles out of the arena. That was an encouraging sign. We were still hopeful he might recover with only minimal long-term damage to his feet.

Two weeks in we stopped icing his feet. Hurray! I still had to get up a couple of times during the night to give him his next round of meds, but at least I didn’t have to wrestle with the repacking of the ice boots. We tried to reduce the level of painkillers. The result: he could barely walk. We changed meds and got him stabilized back to where he had been, but he continued to be a mystery. The x-rays simply weren’t that bad. Why was he continuing to show this degree of pain?

After two months he was no better, but he was also no worse. I was scheduled to be out of the country for a week. I left on a Wednesday. Friday I got an email from Ann. She had tried to reach me by phone, but the contact number wasn’t working. Sindri was colicing.

More nightmare.

I borrowed a cell phone and made the overseas call. It was the middle of the night for Ann, but I knew she would be up. She told me they weren’t sure what was going on, and she didn’t know what to do.

I heard myself saying if you think surgery is an option, ship him sooner rather than later. Already, by waiting it might be too late.

I also heard myself telling her in more detail about Robin, about the cost of the surgery and the aftercare, about the risk to the feet in any horse, and the increased risk in a horse who already had laminitis.

I heard myself saying she should call Bob and get the trailer hooked up. I knew it was the middle of the night, but he wouldn’t mind. If she thought she wanted to go forward with treatment, the sooner they got to a hospital the better. She should ship him while he was still able to go.

We talked for a few more minutes. We both wanted the same thing for Sindri. We wanted to give him a chance, but not if it meant condemning him to a lifetime of chronic pain.

I hung up, and pretended that everything was normal while I taught the morning sessions. When it was eight o’clock back home, I called again. The vets had recommended that Ann send him to our local clinic. It looked as though the colic would resolve medically, but they wanted to be able to support him with fluids and monitor him more closely. They had trailered Sindri over mid-morning to the clinic. I kept checking my emails waiting for word of what was going on.

Sometime overnight things changed dramatically. He began to reflux, a sign that there was a blockage somewhere. Then the reflux slowed, but he became very painful, bucking and spinning in his stall.

His condition had shifted from a medical colic to an emergency surgery, but he was still an hour from the hospital. Ann and I talked on the phone. We both decided to send him for surgery. It was so hard being so far away. I knew the risks far better than Ann. I had seen foundered horses. What were we doing? But we had to give him a chance.

Sindri made it to the hospital, but like Robin, he had to wait for another horse to come out of surgery. He seemed to stabilize, and it was looking as though he might resolve medically, but then the reflux started again, and the decision had to be made. Ann got the call and gave her permission to go ahead.

On the other side of the ocean I waited for news.

Sindri’s surgery was shorter than Robin’s and had a better outcome. His intestine was inflamed. They found signs of what might have been constrictions, but if there had been a blockage, it had resolved.

I flew home on Monday. I was anxious to get in and get down to see Sindri. I was hoping he would still be alive, that I wasn’t flying home to a dead horse. United Airlines let me down. The last leg of my trip was cancelled, and I had to spend the night in Newark. I didn’t get home until mid-day on Tuesday.

Sindri waited for me.

He was in the same stall that Robin had started out in. I almost didn’t recognize him as I walked up to his stall. Unlike Robin, he looked like the very sick horse that he was. His thick mane and forelock were braided to keep them out of the way of the catheter and fluid lines. It was like looking at someone who you’ve only known with a beard. Oh, that’s what you look like!

All four feet were in ice boots. He was clearly in a lot of pain, both from the surgery and his feet. The surgeon stopped by to update me on what they had found. He sounded hopeful that Sindri would recover well from the surgery. I looked at the way he was standing and wondered.

Over the next few days Sindri took us on a downward spiral. He wasn’t eating. Fresh x-rays showed us that we were now dealing with a rotation of his coffin bone, and his blood work was pointing us in the direction of liver damage.

I had stopped working on my book when Robin had gotten better. Now I brought it out again. Every morning I worked on it, and every afternoon Ann and I drove down to visit with Sindri. The vets started him on IV nutrition to try to reverse the liver damage. Slowly he began to eat a little on his own. Now instead of rejecting the handfuls of hay that he was offered, he was asking for more.

Mid-week a mini donkey moved in to the stall directly across from Sindri. While Sindri’s condition slowly improved, the donkey’s declined. He was clearly much loved. His family came often to see him. His liver was failing, but he wasn’t as lucky as Sindri. The vets weren’t able to stop the progression of his disease. I heard the vets discussing the possibilities with his owners. Epm had been ruled out, along with West Nile. They weren’t sure what they were dealing with, or what more they could do.

It was hard to celebrate Sindri’s growing appetite knowing that across the hall there were only tears.

The vets began to talk about Sindri going home. If he meets this milestone, maybe by Wednesday. Then it was Thursday, then Friday. Finally the call came early Saturday morning. Sindri had been cleared, we could take him home.

When we arrived the mini donkey was on his side resting on a thick mat. He was having a seizure.

Across the hall Sindri was looking bright and very much ready to go home. We were using a borrowed stock trailer that didn’t have a ramp. I was concerned that Sindri might be reluctant to step up into the trailer. I needn’t have worried. Sindri was ready to go home. One of the interns took him out before I realized he was even out of his stall. He was already on the trailer by the time I got outside. Good Sindri!

He got off just as easily and walked surprisingly well up to the barn. But over the next couple of days that changed. Walking was reduced to a slow hobble.

I’ve been trimming my horses feet for the last couple of years. That means when something like this happens, you don’t have a farrier available to help you. My vet called in a favor and arranged for one of the best farriers in the area to come help us. Together they decided that the best option for Sindri were wooden clogs. The clogs are built up of layers of wood laminated together. They let the horse’s foot roll over in any direction that is comfortable, and apparently they can provide almost instant relief to some laminitic horses.

The farrier and my vet came out together to put the clogs on. They took x-rays first. The x-rays showed clearly why Sindri’s feet had become so much more painful. The last set of x-rays taken at the hospital had indicated that he still had good depth of sole. On the new x-rays the coffin bone on both front feet had rotated even more and was now pressing down on the sole. We had run out of foot.

I’m glad it was an experienced farrier who trimmed Sindri’s foot that day and not me. The sole was separating at the toe leaving a long line of exposed soft tissue. There was no possibility of putting the clogs on. The farrier made some temporary pads to protect his feet. Sindri was so good to stand for the trimming and for all the fussing with his feet.

We had been keeping him on a sand stall, but with his feet so open, the sand had to go. We put Sindri temporarily in one of the other stalls, while I dug out load after load of sand. Sand is amazing how it gets into all the cracks and crevasses and refuses to come out. I swept until sweeping was doing no good. Then I got out my vacuum – yes the barn has a vacuum. I bought it originally for my house, but somehow it ended up at the barn instead. When the vacuum wasn’t getting anything more, I washed the mats. I had just spent two weeks in a vet hospital. They had set the bar high for cleaning a stall!

Finally it was ready for shavings – four bags to create a wonderfully deep, soft bed. Sindri was going into a luxury apartment! Once he had hobbled from Fengur’s stall to his own, he lay flat out on this new thick mattress and fell into an exhausted sleep.

We ordered boots for Sindri. They came by overnight express the following day, and we transferred him from the styrofoam pads he had been in to the protective and much more supportive boot. Every day Ann helped me change his wraps and reapply a sugar and betadine mix to the soles of his feet.

A week later Sindri’s feet were less painful. The soles were beginning to grow in and cover up the exposed soft tissue, but I knew we still had a long road ahead of us. The goal was to make him comfortable. He was still bright eyed, and engaged with us. He was telling us it was okay to keep going. As long as his eyes were bright, we would keep going on. Ann couldn’t say no to the surgery, anymore than I could say no to Robin’s. So here we were in a place we never wanted to be with any of our beloved horses.

I always wanted to live in a barn with my horses. I never expected I would be doing so under such circumstances. Once again, I turned the tack room into my full time office and living quarters. While I worked on the computer, I could keep an eye on Sindri. Each afternoon Peregrine and Robin would have a nap standing side by side in the aisle next to Sindri’s stall. Fengur, our other Icelandic, was generally outside having a sunbath in the barn yard. And I was in my “stall”, keeping watch.

Sindri’s coffin bones stabilized. With good care, a good farrier, and a lot of luck, his feet began to heal. I kept writing throughout all of this.

Some people take up drinking when times are rough. Other people go shopping or remodel their homes. I, apparently, write books. The first draft of the book was begun during Robin’s stay in hospital. And it was finished during Sindri’s.

The book has been finished for a long time, but I have been undecided what I want to do with it. Robin is still doing well, but we lost Sindri the day after Christmas 2014. He coliced again, and this time it was clear it was the end. When I led him for the last time out of the barn, he walked sound. We had beaten the founder, but we couldn’t beat the colics. Perhaps six months of pain killers and other medications had just been too much for him.

I set the book aside. It’s been sitting in my computer, waiting. I wasn’t sure for what. I really haven’t wanted to publish it as a book, but if not that, what? The book I have written was given to me by my horses. It has grown out of lessons Peregrine and the others have been teaching me. I wanted to share it, but I wasn’t sure how.

My decision has been to do something very old fashioned with it, but with a modern twist. I’m borrowing an idea from the nineteenth century. Charles Dickens published his books in serial form. Before they were turned into books that could be read cover to cover, they came out in weekly installments in inexpensive periodicals. That meant his stories could be more widely read, but imagine having to wait a whole week to find out what twist the next chapter would bring.

I’m going to do something similar, but instead of using a printed magazine, I’m going to publish my book here on this blog, section by section. I know we all live busy lives so I’ll space the publishing of these articles out so they don’t become overwhelming.

So what is this book about? The simplest answer is play.

I have always played with training. I have always told people to go “play” with an exercise. I send them home to “play with ideas”, not to “work on a lesson.” Play has been central to my life, but work can overcome that. It has taken a lot of work to bring clicker training into the horse community. My horses were always there reminding me that play is more powerful.

So it was right that a book about play would emerge at a time when I was most focused on my horses. It was written first and foremost for my horses, perhaps you could even say by my horses. It is a gift from them to you. I hope you enjoy it.

Alexandra Kurland

January 2 2016

Before I begin, I want to extend my great thanks to Dr. Naile and all the vets and staff at Oakencroft Veterinary clinic, and to the surgeons and staff at Rhinebeck Equine Hospital for the good care they gave to Robin and Sindri.

Also, a very great thanks to Mary Arena, who helped us enormously in caring for the horses, especially when I was away. I would not have been able to travel if Mary had not been willing to step in and help. Her contribution has always been greatly appreciated and always will be. You never say thank you enough to people, but, Mary, I get to say thank you here.

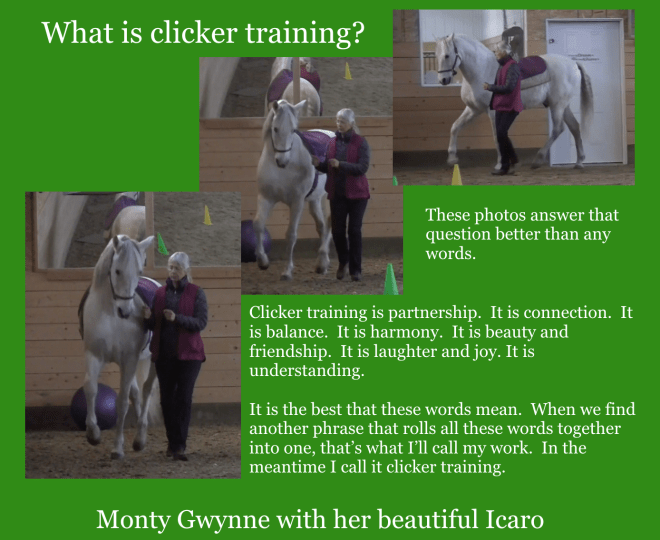

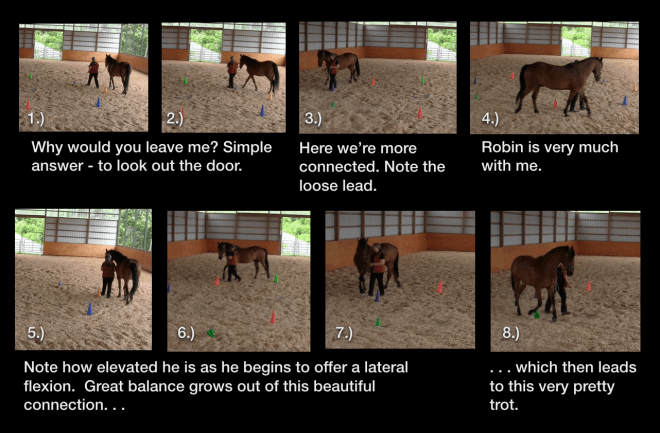

Note: What this book is, and what it is not. In clicker training we learn to shift our focus from the unwanted behavior. We want to focus on what we want the learner TO DO. So it seems odd to be saying what this book is not. It is not a “how-to” guide to clicker training. I’ve written those books, produced those DVDS, written that on-line course. If you are new to clicker training and need the nuts and bolts of how to get started, I will direct you to those resources. You can find them all via my web site: theclickercenter.com.

So what is this book? And who is it for? The second question is easy to answer. It’s for you – especially if you have animals in your life, and you’re interested in training.

Over the past twenty plus years I’ve been pushing the boundaries of what can be done with clicker training. How do we use it? How do we think about it? What is our current understanding of cues, chains, reinforcement schedules, etc., and how has that changed over the years?

This book explores some of the areas that exploration has taken me. We’ll be going well beyond the basics of clicker training. I want to share with you the differences that make a difference – that transform you from a follower of recipes into a creative, inventive trainer. Play is the transformer. In the articles that follow you’ll discover what I mean by that.

I won’t be posting every day. That would be overwhelming to you and to me. Tomorrow is a travel day, so I’m not sure when I’ll be posting the next blog. It will depend in part upon my internet access. I will be putting you instead on an intermittent reinforcement schedule. If you want to be notified when new posts are published, please sign up to follow this blog.

Coming soon: Part 1: Why Play?

Copyright 2016 All Rights Reserved. I know on the internet how easy it is to pass posts around. I certainly wrote this to share, and I hope you will share the link to these posts with others, but please respect the copyright restrictions on these articles. If you wish to reprint them, please contact me for permission. (kurlanda@crisny.org)

I’m writing this section about the ABCs of training sitting on the inner deck of my barn. From my vantage point I can see Peregrine and Robin lying down in the arena enjoying a morning nap.

I’m writing this section about the ABCs of training sitting on the inner deck of my barn. From my vantage point I can see Peregrine and Robin lying down in the arena enjoying a morning nap. Robin is resting more upright, his nose buried in the shavings as he falls into a deep sleep.

Robin is resting more upright, his nose buried in the shavings as he falls into a deep sleep.

We stop worrying so much about how we look to others. In imaginative play we may even become a different “self”. When you’re trying to learn to ride and you have an instructor barking commands at you treating your lesson more like military boot camp than something you’ve chosen to do for fun, you’ll be a long way from a PLAY state. Barked commands create FEAR and make the learner more self-conscious – not less. To promote the best mental state for learning and retaining information, we want to be PLAY full.

We stop worrying so much about how we look to others. In imaginative play we may even become a different “self”. When you’re trying to learn to ride and you have an instructor barking commands at you treating your lesson more like military boot camp than something you’ve chosen to do for fun, you’ll be a long way from a PLAY state. Barked commands create FEAR and make the learner more self-conscious – not less. To promote the best mental state for learning and retaining information, we want to be PLAY full.