Metaphor: noun – a thing regarded as representative or symbolic of something else, especially something abstract.

Which image describes you? Are you: set in stone; or growing and changeable like an oak sprouting from an acorn?

Do you believe that intellectual abilities or athletic talent are something you’re born with? If you weren’t born smart, or fast, or coordinated – oh well, you just aren’t going to be able to excel.

believe that intellectual abilities or athletic talent are something you’re born with? If you weren’t born smart, or fast, or coordinated – oh well, you just aren’t going to be able to excel.

Carol Dweck, a psychologist teaching at Stanford University, calls this a Fixed Mindset.

Or do you believe in neuroplasticity? Do you believe that your abilities are not fixed rigidly by your genes but can be developed over time through deliberate practice?

Dweck calls this a growth mindset.

Dweck has done a number of fascinating studies showing the impact that these two mindsets have on performance. In one study involving 400 5th grade students from all over the US, students were brought into a room one at a time and given ten problems to solve. On completion the students in one group were praised for their intelligence. They were told they had achieved a really good score which meant they must be very smart. The students in the second group were praised for their effort. They were told they had a really good score which meant they must have worked really hard.

The students were then given another test, but this time they could choose which test to take. The first option contained a set of problems that were similar to the first set. They were told they would almost certainly do well on this test. Or they could work on a much more challenging and difficult set of problems that gave them the opportunity to learn and grow.

Can you guess what the results were?

If you said the students who were praised for their intelligence chose the easier test, you would be absolutely right. 67% chose this option. In dramatic contrast 92% of the students who were praised for their effort chose the more challenging test.

One little phrase: you’re really smart or you worked really hard changed the choice they made. Here’s the explanation Dweck gives for this difference:

The children who were praised for their intelligence thought that’s why others admired them. They didn’t want to do anything that would show that they weren’t really that smart, so they played it safe. They developed what Dweck refers to as a Fixed Mindset. Instead of challenging themselves with the tougher set of problems, they chose the option that would support the self-belief that they were smart. The result was they limited the growth of their talents.

The students who were praised for their effort received a very different message. They heard that it was their hard work and the strategies that they chose that created the good result. Instead of thinking that mistakes would show that they weren’t smart and talented, they looked at challenges as opportunities to grow and become more talented.

In the next part of the study all the students were given a truly challenging test that was beyond their current abilities. The students who had been praised for being really smart became frustrated and gave up early. The students in the second group worked longer and reported enjoying the process.

In the last phase of the study the students were given a test that was at the same level of difficulty as the first test. The students who had been told they were really smart showed a decline of on average 20% in their scores while the students who had been praised for their effort raised their score on average by 30%. That’s a whopping 50% difference between the two groups – caused by just a few simple and in both cases well-meaning words.

Changing Mindsets

So what do you do with this information? How do you help someone shift from the limitations a fixed mindset creates to the open-ended possibilities of a growth mindset?

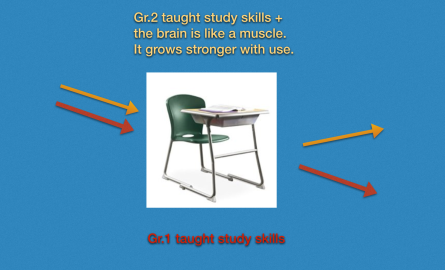

Dweck conducted another study that sought to answer this question. She and her colleagues took a group of 7th graders who were doing poorly in math and divided them into two groups.

The first group was given an intervention in which they were taught better study skills.

The second group was taught the same study skills, but they were also taught that the brain was like a muscle. It got stronger with use. When they were working through a challenging problem, the neurons in their brains were forming new connections. Those new neural synapses were helping them to become smarter.

The results of these two interventions created very different results. The first group continued to show a decline in their math scores, while the second group improved.

Metaphor Matters

Metaphor Matters

Current research in neuroscience has given us the metaphor of neuroplasticity. Our brains continue to grow, make new connections, change in response to the learning challenges we take on. When a student is faced with a difficult math problem, instead of cringing away from it, she tackles it with enthusiasm. When she hits a stumbling block instead of quitting in frustration, she thinks of the new neural connections that are forming in her brain, making her smarter and able to tackle even tougher problems. This is what Dweck’s study showed.

Metaphor matters. So what metaphors do you have? What works for you? And how does this carry over to your horses?

The Mindset Trap

Do you have a fixed mindset for yourself? For your horse?

Years ago I had a client who was frustrated by the length and shape of her thighs. “If only they were longer, if only they were thinner,” she would lament, “then she would be able to ride the way she wanted to.” But alas, she was short and no matter what she did, she would never be the tall, long-legged, naturally-gifted rider she envied. Her fixed mindset kept her stuck. She was a good rider, but she was never able to enjoy her achievements.

She had a similar fixed outlook for her horse. She couldn’t afford the big, fancy warmblood the long-legged riders all had. She could only afford an off-the-track thoroughbred with poor feet and some undiagnosed hind end issues. She was constantly feeling frustrated and stuck. How could she ever progress given the way the cards were stacked up against her?

My thoroughbred was never on the track, but he certainly had major hind end issues, and yet I didn’t crash up against the same glass ceiling that hung permanently over my client’s head. My passion was learning. Peregrine presented me with many struggles and many frustrations, but always with the opportunity to learn. In many ways because Peregrine had such severe physical issues, he freed me up to experiment. I’ve encountered so many people who have finally bought the horse of their dreams. They have a beautifully trained, athletic horse who can carry them forward to their performance goals – and yet they are frozen. They become completely dependent upon their trainers, unable to risk any experimentation for fear that they will mess up their horse. In Carol Dweck’s studies the performance scores of the children with fixed mindsets declined. I’ve seen the same thing with the riders who are trapped by fixed-mindset belief systems.

The Journey to Excellence

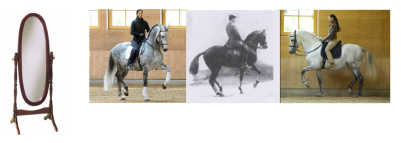

Where did this trot come from?

This warmblood stallion is expected to be brilliant.

Would you at first glance expect the same of this horse?

So again – where does talent come from?

You could answer this by saying that his owner, Natalie, is a naturally gifted animal trainer. She’s one of those people who just seems to have a way with animals, who can bring out good things in every animal she works with, be it a horse, dog, cat, or guinea pig.

Or you could say that it comes from Natalie’s willingness to work hard no matter the conditions. Many is the video she’s sent me where she’s out in the snow on a cold winter day training her horse. Others would be inside by the fire, but she continues to work regardless of the weather. Her talent comes from that hard work diligently applied over a long period of time.

But that still leaves the question: where does this growth mindset come from? And how can you strengthen your own growth mindset so you can be on your own journey to excellence?

Are Your Metaphors Up To Date?

Are your metaphors up to date, or are you stuck in old belief systems that no longer serve you well? Science changes. Have you changed along with it, or do you still believe in old, outdated theories?

What we were taught in grade school in so many cases no longer applies. Consider genetics. In school I remember learning about Lamarck and his giraffes.

It was a lovely, simple metaphor. The giraffes stretched higher and higher to reach the upper branches in a tree. As a result, their necks grew longer, and they passed on this trait to their upward-reaching offspring.

It was a lovely, simple metaphor. The giraffes stretched higher and higher to reach the upper branches in a tree. As a result, their necks grew longer, and they passed on this trait to their upward-reaching offspring.

We were taught to laugh at Lamarck. What a silly notion. Much better was Mendel and his peas. We learned about recessive and dominant traits, and we learned how to do the formulas that would predict how many peas would be short and how many would be tall.

Mendel’s was also a lovely, simple metaphor, only now with epigenetics coming on the scene we are discovering that maybe we will have to dust off poor old Lamarck and take another look at his metaphors.

Mendel’s was also a lovely, simple metaphor, only now with epigenetics coming on the scene we are discovering that maybe we will have to dust off poor old Lamarck and take another look at his metaphors.

Science Changes and So Must We

The point is our ideas about how the world works change over time. We come up with new, better metaphors to describe our current, best guess at how things work. We use these metaphors in many ways. And sometimes we go back and dust off old metaphors even when we know they aren’t correct.

In 2005 economist, Thomas Friedman, wrote “The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century”. You might well ask: did Friedman not know that Christopher Columbus didn’t fall off the edge of the world? In grade school had he not learned about Magellan circumnavigating the globe? Did he truly believe the world was flat!? Of course not. He was using the image of a flat planet as a powerful metaphor to help us understand economic globalization. Because we know the world really is round, Friedman’s metaphor is all the more powerful.

In 2005 economist, Thomas Friedman, wrote “The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century”. You might well ask: did Friedman not know that Christopher Columbus didn’t fall off the edge of the world? In grade school had he not learned about Magellan circumnavigating the globe? Did he truly believe the world was flat!? Of course not. He was using the image of a flat planet as a powerful metaphor to help us understand economic globalization. Because we know the world really is round, Friedman’s metaphor is all the more powerful.

This to me is a great example of how we use metaphors and how role of science is to provide us with new, better, different ways of perceiving the world.

If I were trying to find the cure for cancer, I might take umbrage at this view of science. I would be looking for The Truth – whatever that means. Instead what I want from science is a more useful story.

I want images and metaphors that help me:

- Better predict how an animal is going to behave, especially in response to my actions.

- Provide me with better ways to explain my training choices to others.

- Motivate people to develop their own skills so they can become better caregivers and trainers for their animals.

The Talent Metaphor

The Talent Metaphor

I can’t talk about the question of where talent comes from without bringing up Daniel Coyle and his book, The Talent Code.

Coyle is not a scientist, but like me he is a user of the metaphors science provides. His book is brimming over with great metaphors, many of which I have been borrowing of late. In The Talent Code, Coyle poses the key question: where does talent come from?

The old metaphor was talent was something you were born with. Mozart was born a musical genius. The fact that his father was also a musician and began rigorously teaching his son from infancy on is irrelevant to the metaphor of genius as an innate gift. This image of Mozart the musical genius is one many people firmly believe.

The OLD metaphor: talent is something you are born with. If you aren’t one of the gifted few – oh well, too bad.

The NEW metaphor: talent is the product of deep practice techniques that develop well-myelinated nerve fibers. If you aren’t one of the gifted few – don’t give up, just find better practice strategies for achieving your goals.

The Myelin Metaphor

In the neuroscience courses I took way back when I was in school myelin got a cursory mention, nothing more. Myelin insulated the nerve fibers – end of story. No one really talked about what this really meant. Why was it important for nerve fibers to be insulated? What did that do for a nerve fiber? If I thought about it at all it was to picture a nerve cell wrapped in a bundle of attic insulation. I never really thought why a nerve cell needed to be kept warm! It was a word that was tossed out and then quickly glossed over. All the focus was on the nerve cells themselves not the myelin that coated them.

In the neuroscience courses I took way back when I was in school myelin got a cursory mention, nothing more. Myelin insulated the nerve fibers – end of story. No one really talked about what this really meant. Why was it important for nerve fibers to be insulated? What did that do for a nerve fiber? If I thought about it at all it was to picture a nerve cell wrapped in a bundle of attic insulation. I never really thought why a nerve cell needed to be kept warm! It was a word that was tossed out and then quickly glossed over. All the focus was on the nerve cells themselves not the myelin that coated them.

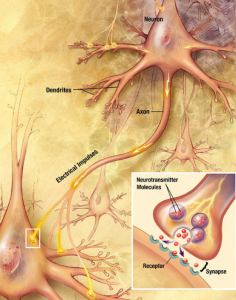

So here’s the modern, updated short course on neuroscience – with apologies to any neuroscientists who may be reading this:

Put very simply nerve fibers carry electrical impulses through a circuit.

Myelin wraps around those nerve fibers, insulating them so the electrical impulses

don’t leak out.

This illustration depicts the multiple layers of myelin surrounding the inner nerve axon. The thicker the myelin sheath – the faster and more efficient the nerve fiber becomes.

This illustration depicts the multiple layers of myelin surrounding the inner nerve axon. The thicker the myelin sheath – the faster and more efficient the nerve fiber becomes.

When nerve cells fire, specialized glial cells respond by wrapping layers of myelin around that neural circuit. The thicker the myelin gets, the better it insulates, and the faster the electrical impulse is transmitted.

Think of the difference in speed between the old dial-up modems and the new high-speed fiber optic cables of today. The sweetest sound in the morning used to be the high-pitched squeal that signaled a successful dial-up connection. I remember the slow load times and the long waits for even simple functions. Very little of what I use the internet for today would be possible at those old, slow speeds.

Think of the difference in speed between the old dial-up modems and the new high-speed fiber optic cables of today. The sweetest sound in the morning used to be the high-pitched squeal that signaled a successful dial-up connection. I remember the slow load times and the long waits for even simple functions. Very little of what I use the internet for today would be possible at those old, slow speeds.

Just as faster connections give us a much more talented internet, faster nerve fibers give us a much more talented individual. Here’s where the myelin metaphor takes us:

- Every thought, action, or emotion depends upon a precisely timed electrical signal traveling at high speeds through a chain of neurons.

- Myelin insulates the fibers and increases signal strength, speed and accuracy.

- The more a particular circuit is fired, the more myelin optimizes that circuit, and the stronger, faster, and more fluent our movements and thoughts become.

This doesn’t happen just for the talented few. Myelin is universal. We all grow it, and it impacts all skills – physical, emotional, and intellectual. Understanding the role myelin plays in nerve functions gives us a metaphor to create growth mindsets.

Questions

So let’s ask:

How do you build super-fast, well-insulated neural networks?

The answer, according to Coyle, is you focus on your errors, but you do it in a very structured and specific way that he refers to as Deep Practice. I wrote about this in detail in my recent post: In Search of Excellence: Effective Practice (Nov. 16, 2014).

How do you build skills in an activity where mistakes can get you killed?

The answer here is you use simulators.

There are many very high-tech riding simulators now on the market. This is not the kind of simulator I have in mind. I’m thinking of some much more low-tech, but still very powerful ways of developing your skills separate from your horse. Again, I wrote about this in detail in my recent post.

In brief: practicing your rope handling skills first with a “human horse” is a great way to develop your skills. It keeps you safe while you are learning, and it lets you experience the effect of different actions from both the horse’s and the handler’s perspective.

When you combine “equine simulators” with the new research on myelin, you get people focusing with much greater intent on the work. Just like the students in Carol Dweck’s study whose scores improved after they were taught about better study skills and neural plasticity, the riders who engaged in horse simulator exercises after learning about myelin, deep practice techniques and the connection to talent hotspots, showed much more engagement in the process.

When you combine “equine simulators” with the new research on myelin, you get people focusing with much greater intent on the work. Just like the students in Carol Dweck’s study whose scores improved after they were taught about better study skills and neural plasticity, the riders who engaged in horse simulator exercises after learning about myelin, deep practice techniques and the connection to talent hotspots, showed much more engagement in the process.

Seeing these connections has led me to my new favorite training metaphor:

Deep practice through myelin mastery creates growth mindsets and leads to excellence.

Deep Practice

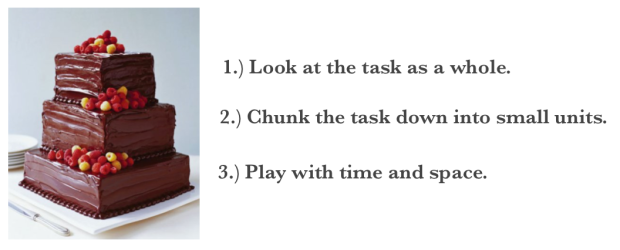

It turns out that there are three tiers to Deep Practice. I described them in my previous post, but we’re going to revisit them here. I’ll be illustrating them with lots of new metaphors. Hopefully you’ll find them of value.

For each tier I’ll give the overall definition, then I’ll look at how this applies directly to clicker training, and then specifically to horse training.

1.) Look at the task as a whole:

You have to have some sense of what you are building before you can begin.

The Translation to Clicker Training: Training Plans.

Good shapers have a training plan that takes them step by step towards their goal behavior. Often the analogy of a staircase is used to describe this planning process.

The Translation to Horses:

Find a look that pleases your eye. Collect images that inspire you. Paste them on your refrigerator, your bathroom mirror. Decorate your desk at work with them. Put them by your bedside table. Make them your screen saver. Create a gallery of images that make you smile and say: I want that.

Another Great Metaphor: Mirror Neurons

Another Great Metaphor: Mirror Neurons

We are wired to imitate. That’s been another interesting discovery – mirror neurons. They fire as we watch someone else perform. When I’m coaching someone, I don’t just see their ride. I feel it.

We are wired to imitate. That’s been another interesting discovery – mirror neurons. They fire as we watch someone else perform. When I’m coaching someone, I don’t just see their ride. I feel it.

Filling your life with the images that inspire will allow this imitating process to occur almost without your being aware of it. But because we are wired to imitate be care-full of the images you watch.

Normally this is written careful, but I want to emphasize this point. Be full of care. Especially today with such easy access to all kinds of images via youtube, be care-full what you watch. If you find within a few seconds of watching a dressage ride, that you aren’t liking what you see, turn it off. You don’t need to watch it through to the end.

When you focus on what you don’t like, you’re still absorbing those images and myelinating those circuits.

Be Care-Full what you watch.

Instead find images you like. Linger over them. Let them permeate through you and become part of you.

When you practice, you will find yourself mirroring those images.

Break each task down into small units.

When you divide a task up into very small units, it is easier to notice the small errors that exist in each of those units. Highlighting the errors lets you adjust, correct, perfect each of those small units.

The Translation to Clicker Training: Thin Slicing.

For every step that you find, no matter how small it may seem, there is ALWAYS a smaller  step that you can break something down into. You want to keep thin slicing and thin slicing until you find a step where you can get a consistent, clean loop of behavior. If you find bobbles, mistakes, resistance, the slice you’re looking at is still too large.

step that you can break something down into. You want to keep thin slicing and thin slicing until you find a step where you can get a consistent, clean loop of behavior. If you find bobbles, mistakes, resistance, the slice you’re looking at is still too large.

Looking at training from the perspective of myelin makes clean loops all the more important. You want to be insulating pathways that fire off patterns you want to build. If you allow in little bobbles, little bits of almost-good-enough-but-not-quite, those errors will become insulated along with everything else. They will become stronger, easier to access, harder to avoid.

The myelin model also gives us another way to look at shaping. Especially when people are  new to clicker training, they often begin with a broad brush approach to the behaviors they are clicking. They start with a general approximation and then gradually refine their criteria towards the more polished, goal behavior. If you are after consistent, high-quality performance, the myelin metaphor suggests that this may not be the best strategy. Instead it tells us why you may find old pieces of unwanted behavior creeping back into your training. Through this broad-brush shaping process those old patterns will have become well myelinated right along with the patterns you want to keep.

new to clicker training, they often begin with a broad brush approach to the behaviors they are clicking. They start with a general approximation and then gradually refine their criteria towards the more polished, goal behavior. If you are after consistent, high-quality performance, the myelin metaphor suggests that this may not be the best strategy. Instead it tells us why you may find old pieces of unwanted behavior creeping back into your training. Through this broad-brush shaping process those old patterns will have become well myelinated right along with the patterns you want to keep.

Training Mantras

This myelin model of shaping gives me some new favorite training mantras to go along with my new favorite training metaphors.

Be Care-Full what you myelinate.

Remember myelin wraps. It doesn’t unwrap.

At the risk of sounding like Benjamin Franklin, what this translates to is:

A habit formed is a habit kept.

The Translation to Horses

Horses notice everything. They are masters at reading body language. How you stand, how your weight shifts, even how you breath, all these details will be noticed by your horse. One of the common tripping up points many new handlers have is their body language is telling the horse something very different from their intended message. Taking the time to learn about your own balance means you will be giving one consistent message – not two conflicting ones.

In clinics we explore balance through a series of awareness exercises that are designed to help you communicate more effectively with your horse. Movement is slowed down into tiny weight shifts. I want people to experience their balance at a micro level. It is observe, adjust, perfect. We are building skills myelin layer by myelin layer.

We move from these awareness exercises to working with “human horses”. Handlers develop their skills working with a partner who can give them verbal feedback and where mistakes are welcome. What happens when you slide down a lead with tension in your shoulders? Let’s find out. What does your “human horse” think of this? Now release that  tension and see what difference – if any – it makes. These training games turn us into “mad scientists”. We can ask questions, experiment, try different strategies. These same “mistakes” made with a horse could create frustration, even injuries. Mistakes made with your “human horse” are part of the learning process. They are part of the growth mindset that leads to excellence.

tension and see what difference – if any – it makes. These training games turn us into “mad scientists”. We can ask questions, experiment, try different strategies. These same “mistakes” made with a horse could create frustration, even injuries. Mistakes made with your “human horse” are part of the learning process. They are part of the growth mindset that leads to excellence.

The Click Creates Steps

Chunking down continues once you are back with your horse. Every time you click, you are creating a step in the training. With your new-found awareness of your own balance, you can ask more subtle, detail-oriented questions of your horse. Beginners shape on a macro level. They ask a horse to back, and they click as they see him take a full step.

Think about what this means for the horse. Often the timing of the click is late. The horse is already putting his foot down by the time the handler is clicking. So the handler wants movement, but the horse thinks he’s being reinforced for stopping. Oh dear.

Even more confusing the next time the horse gets clicked it’s for taking a step back with his other front foot. That’s a different behavior.

The micro trainer is more aware of small details. She begins by clicking for just a shift of balance. Her timing is good and the behavior is repeatable. The circuits she’s insulating create a clean, consistent final behavior.

Playing with Time

Detecting mistakes is essential for making progress. This error-focused element of deep practice is achieved by playing with time. Movement is slowed down so small bobbles and losses of balance can be detected and corrected.

Daniel Coyle described practice sessions at a music school where students played the music so slowly it became unintelligible. By slowing down and drawing out each note, they were able to notice slight errors in their technique. If their performance goals had been to play just for themselves and a few friends, those errors might not matter, but when you are training for the world’s great concert halls, they most definitely do.

Daniel Coyle described practice sessions at a music school where students played the music so slowly it became unintelligible. By slowing down and drawing out each note, they were able to notice slight errors in their technique. If their performance goals had been to play just for themselves and a few friends, those errors might not matter, but when you are training for the world’s great concert halls, they most definitely do.

So again it is highlight, adjust, perfect. The myelin model tells us that this attention to detail creates clean, highly polished skills.

The Translation to Clicker Training

Slowing an action down lets you notice

and attend to errors. Focusing on

errors at first sounds like the opposite

of clicker training. We want to focus

on what we want the animal TO DO,

not the unwanted behavior.

But that’s at the MACRO level.

At the macro level I do want to focus on what I want my horse to do. I can’t train a negative. Saying I don’t want my horse crowding into my space, doesn’t tell my horse what he CAN do. I can punish the unwanted behavior, but unless I provide my horse with an acceptable alternative, I’m leaving him in a guessing game. It’s up to him to figure out how to stay out of trouble. That’s not only bad training, it’s incredibly unfair. So I need to teach positive actions. What is the behavior I WANT to see? If my horse stops crowding me by bolting off, I haven’t solved anything. I’ve just replaced one unwanted behavior with another. Focusing on these undesirable actions, turns me into a reactive trainer. I’ll be forever chasing after these unwanted behaviors, trying to stomp out brush fires before they spread.

What I want to do instead is create an overall macro picture of my perfect horse and then train on a micro level.

At the MICRO level I can notice the small bobbles and loss of balance that may be part of the root cause of the behavior problem. I can refine my criteria even more until I have a clean, error-free loop of behavior.

At the MICRO level I can notice the small bobbles and loss of balance that may be part of the root cause of the behavior problem. I can refine my criteria even more until I have a clean, error-free loop of behavior.

So it’s – highlight, adjust, click, reinforce, repeat – until the loop is clean.

Again, the myelin model says that this attention to detail will create the clean, consistent behavior I am after.

Chunking down to micro creates thin slicing and that in turn leads to excellence.

The Translation to Horses

When you are first experimenting with clicker training, it’s tempting to jump right in and rush past all the details that I find so fascinating. Initially the focus is on macro behaviors. It’s easy. It’s fun – that is, until your horse becomes frustrated by the lack of clarity. Details do matter. Every time you click and give your horse a treat just when he’s falling onto his inside shoulder, you are insulating circuits that you are not going to want.

Remember

- Myelin wraps nerve fibers.

- It insulates them well to build strong, high-speed habits.

- Myelin wraps. It doesn’t unwrap.

So you want to build good habits sooner rather than later.

The myelin pathways I am strengthening by playing with time lead to excellence.

But so far I have only focused on technical skills. To improve my ability to respond to the unexpected I’m going to play with space, as well as time.

Playing with Space

In “The Talent Code” Daniel Coyle used the example of the incredible ball-handling skills Brazilian soccer players develop by playing a game called futsal. Instead of practicing on the over-sized expanse of a soccer field, young players build their skills in a space that’s the size of a tennis or basketball court.

Futsal Court

A futsal player can make contact with the ball 600 percent more than he would in a regular

soccer game. That’s a huge multiplier especially when you add in the age at which

these players are starting out. If the above view of the soccer field looks huge to you,

imagine what it must look like to the average eight year old. That’s a huge area to be running up and down. But compress that space into the length of a tennis court, and now you have many more opportunities to engage with other players. There are more quick decisions to be made and more plays to have. Is it any wonder Brazil is a leader in world-class soccer?

The Translation to Clicker Training

When people first watch clicker training, they are often puzzled by all the stopping for a treat. How is the horse ever going to go anywhere if he is forever stopping? That’s one of the most common questions that gets asked from the outside looking in.

When people first watch clicker training, they are often puzzled by all the stopping for a treat. How is the horse ever going to go anywhere if he is forever stopping? That’s one of the most common questions that gets asked from the outside looking in.

The myelin model of skill building explains why this is more than right. It is the road to excellence.

Clicker training is a skill accelerator. Pick a behavior you’d like to improve. It can be anything – teaching a horse to pick up his feet for cleaning, or a dog to sit, or a bird to come when called. For this example, I’ll use teaching a horse to go from a walk into a canter. In a conventional ride, you would normally ask for the canter and then keep going. Over the course of the ride that means you ask for just handful of canter departs. In contrast a clicker trainer might focus in on just the depart phase of the canter. She’ll ask for the depart and – click – her horse will stop to get his treat. This is what non-clicker trainers find so puzzling. The horse keeps stopping. How is he ever going to go anywhere? But what they aren’t considering is how many canter departs that horse is performing.

Let’s compare the two rides:

Conventional training ride: Clicker-trained ride:

Ride 1: ask for 5 canter departs. Ride 1: ask for 20 canter departs.

After 10 rides: you’ll have 50 canter departs. After 10 rides: you’ll have 200 departs.

That’s quite a difference. So let’s consider:

Which horse is going to understand canter departs better?

Which horse is going to have the better insulated myelin?

Which horse is going to pick up the canter faster, with better balance, without seeming to think about it?

It’s an easy answer: the clicker-trained horse. Of course, you won’t be staying at the level where you only ask for the canter depart and then click. You’ll be gradually expanding your loop to include more strides of canter. But that canter will be built on a solid foundation of myelin-supported departs. This is a horse-related example, but the concept holds no matter the species you are working with. Clicker training is a skill accelerator, and the myelin model of excellence helps to explain why.

The Translation to Horses

The Brazilian soccer players play futsal to improve their skills. All those quick encounters sharpen their ability to respond to the unexpected. What do horse trainers do? They put their horses away and practice their handling skills with other people. At clinics I’ll play the part of the horse by holding the snap end of the lead while the handler practices her rope-handling skills. I can let someone experience a horse who is spooking or pulling on a lead over and over again. I’m good at copying what horses do. I know what it feels like to have a horse leaning in on me, or trying to scoot away. I’m good at “being a horse”. I can slow the movement down, make it less abrupt or less forceful so a new learner isn’t as overwhelmed as she would be by an actual horse. I can lean into her space and see how she responds down the lead. That was too slow, try again. Better. Try again. Now what happens if I make a slight change?

These sessions are comparable to futsal. The handler gets in many more practice rounds so she is better prepared for the real thing. We’re improving her underlying technique and sharpening all the quick decision making that partnering a horse requires.

Metaphors Matter – Myelin Matters

Where does talent come from? I asked that question earlier.

The gift of the gifted lies not in genes but in mindset. That’s what Carol Dweck’s work showed. A simple phrase – you’re so smart versus you worked really hard was enough to change the outcome of a student’s performance.

The gift of the gifted comes from the messages we receive from family and teachers. It comes from chance encounters and life experiences that lead us to discover our own powerful metaphors.

Shortly after I posted my recent article: “In Search of Excellence: Effective Practice” – this is what one of the participants in my on-line course sent to the discussion group:

“This post and the book The Talent Code were really timely for me. With the bad weather arriving and our property turning into a giant bog of soupy clay, I’m down to a 14 by 28 foot covered/dry work area. At first I was hugely disappointed to have to postpone the horses’ work for lack of space, but really when I look at it from the perspective of Alex’s post I have my own little futsal court. I set up a miniature cone circle for bending and a mat at one end for balance work and am going thru the blog post and the course in detail looking for exercises we can use for deep practice.”

Metaphors matter. What are the messages you tell yourself? Are you trapped in a fixed mindset? Or like the person in this next post have you found metaphors that create for you a growth mindset?

“The Talent Code gave me hope that I do not have to be born with particular qualities to be successful. That hard work, intelligent practice and learning do make a difference. At about 12 years old I was told to give up my dream of becoming a professional piano player, as “you are not talented enough”. I was stopped the very moment when I was starting to enjoy the piano playing, when piano playing became a lovely activity for me, and not a burden. Thirty years later I can still feel the pain of “not being talented enough”. When I started to work with horses I was obsessed that I did not have the time, I could never be good enough, and performance was not accessible as “I am not talented”. Oh well, I like to believe that I do not need to be talented, I just need to practice and learn deep enough.

And I have found so much in Alexandra’s course to give me hope. I have practiced what she teaches and I am safer, and also I like to believe that the horses I am in contact with are happier.

So thank you Alexandra for giving me the hope that at my age and experience I can still be successful.”

Metaphors matter. Find the metaphors that open your life and take you to your dreams.

Alexandra Kurland

published Dec. 25, 2014

Happy Holidays Everyone – I wish you the best gift of all – the metaphors that give you a life filled with joy, growth, love – and of course horses!

Please note: If you are new to clicker training and you are looking for how-to instructions, you will find what you need at my web sites: