Cues evolve out of the shaping process.

I chose head lowering to illustrate how this works. In Part 1 I ended with a reminder that there is always more than one way to teach every behavior. I teach head lowering in many different ways. The first, easiest way is through targeting. That’s a good start, but just because you can get head lowering one way doesn’t mean your job is done. The more different ways you can trigger the behavior, the better.

Backing in a Square

You may not see the connection at first, but one of my favorite ways to teach head lowering is via backing in a square. The reason for using this teaching process is because it generates a shift of balance from the forehand onto the horse’s hindquarters. That in turn leads straight to improved performance under saddle. You may not see the connection at first, but this way of asking for head lowering creates a very different balance from the one a horse is normally in when he drops his head. The most frequent form of head lowering occurs when he’s grazing.

Head lowering is taught via backing in a square.

Grazing is a forward-moving exercise. Horses graze by walking slowly forward. They don’t normally graze by walking backwards and eating the grass that they have already stepped on. Grazing forward means they encounter fresh grass that hasn’t yet been crushed underfoot.

Grazing is a forward-moving exercise.

Grazing is forward movement.

Not A Forward-Moving Exercise

The expression for teaching head lowering is: head lowering is not a forward-moving exercise.

At first glance this seems like a very clumsy sentence. What you are saying is your horse can stand still and drop his head. He can also walk backwards and drop his head. So you aren’t saying he can’t move his feet. He just can’t move his feet forward.

You most need head lowering when a horse is nervous. A nervous horse needs to move. If you were to try to ask him to drop his head AND stand still, you would bottle him up way too much. Under this kind of enforced restriction, he might end up exploding like an over-coiled spring.

So you don’t say to this still learning-to-be-calm horse – “Stand still”. You say: “You can move your feet all you want, but I get to choose the direction. If you need to move, you can back up. And to be more precise, you can back in a square.”

It’s best to teach this lesson when your horse is calm. If your horse already understands how to back up in a square, he won’t feel trapped. If something does make him nervous, it will be easier to remind him that backing is a great option, and dropping his head is even better.

Moving the Hips

Backing in a square lets you manage where in your work space you are going to be. If your horse becomes even more nervous the further into your arena he goes, backing in a square lets you stay in the part of the arena he can handle. It also keeps him from backing into other horses, ditches, fences, or the clutter that many of us have around our barnyards. Horses learn very quickly what works. Backing is hard work. It’s not something horses normally choose to do on their own. So if backing straight towards a barbed wire fence gets you to stop asking for backing, guess what your horse will learn fast: point your rear end towards anything sharp, or dangerous, and your human will let you go forward.

You can very quickly teach your horse to back towards ditches, blackberry canes, wild roses, barbed wire, tractors, traffic, the one horse in the group that kicks. You name it and if it’s something you don’t want your horse to back into, that’s what he’ll do.

Backing in a square circumvents that. To back through a turn your horse needs to learn two skills. The first one is obvious. Your horse needs to back up comfortably. You want him to back promptly when you ask, every time you ask. He shouldn’t feel as though he is pulling his feet out of cement. He needs to move back fluidly.

You also need to be able to ask him to bring his hips to the inside, towards you. Most of us know how to send a horse’s hips away from us. If you ask a horse to bring his nose towards you, that will send his hindquarters away from you. This is one of the first things a beginner learns.

Think about the instructions you give to someone who is holding a horse for you while you examine a cut on his hind leg. You tell this person to stay on the same side that you’re on. If the horse gets anxious, even a beginner handler will react by bringing the horse’s head towards her. This will send his hips away. If you were standing on the opposite side of the horse, you’d be knocked over. You might try to push his hips away from you, but the effect the handler has with the lead is much stronger that any push you could give at his hind end.

You can get the horse to send his hips away from you, but that’s not the only direction you can influence. A horse can move his hips in six directions.

Up and down. Think about when he lies down and gets up again.

Forward and back.

To the left and to the right.

You want to be able to ask for each of these six directions, especially the last four. Forward and back are easy. You do that every time you ask your horse to follow beside you on a lead, and to stop and back up.

You’ve already seen how you can send your horse’s hips away from you. Bend his nose towards you as he steps forward. That sends his hips away from you.

To bring his hips toward you, you’ll do the opposite. You’ll bend his head away from you as you ask him to back up. I teach this by asking him to back in a square.

Backing in a Square

If the size is suitable, I like to teach this in a stall. The walls will help your horse understand that you aren’t just asking for backing. You want him to turn. Solving this puzzle helps him become more hind end aware.

Some stalls are just too small or too crowded with feed bins, water buckets, and hay racks to be good work spaces. And some horses just aren’t comfortable in stalls. They may feel crowded by their neighbors or anxious because the rest of the herd is outside. Asking them to work in this kind of confinement isn’t fair or productive.

So the next option is a small paddock, but again there can be problems here. If you are slogging through muddy footing, it may not be safe for you or fair to your horse to ask for backing when you’re both pulling your feet out of ankle deep mud. And it’s certainly not fair to ask him to back towards electric fencing – even if that fencing is turned off.

So another option is to lay out ground poles or cones in a large square, and to use those as the boundary markers. If possible use a fence line for one side of your square.

You don’t have to have a stall or small paddock to teach your horse to back in a square. Here the square is built out of cones.

If I’m using ground poles or cones, I’ll pretend that I’m in a stall. I’ll have a designated “entrance”. I’ll begin by walking my horse into the “stall” and stopping so his nose ends up at the “entrance”. This gives me a reference point to return to after each click.

Initially, I’ll ask my horse to back just a step or two, click!.

As I am reaching for the treat, I’ll step forward.

My horse will also step forward to get his treat so we’ll end up back where we started at the entrance to our “stall”.

“Walking and Chewing Gum”

Feeding so he walks forward to the “entrance” is very important. I don’t want to keep asking my horse to back up without taking him forward again to the front of the stall. We would find ourselves all too quickly confronted with the back wall of the square before we’re ready. The closer I get to the wall that’s behind him, the more reluctant my horse is going to be to back up. He’ll be thinking: “What a stupid human! Can’t she see there’s a wall behind me! I can’t back up any more than this.”

In these two photos I’ve brought Robin in too close to the wall. I’ve left him nowhere to go. When I ask for a turn, he ends up crammed against the wall. This could easily make a less experienced horse feel very nervous.

I don’t want to make a nervous horse feel more nervous because I’m crowding him up against a wall. And I definitely don’t want my horse thinking I’m incompetent and stupid! So instead, before we get too close to the back wall, I’ll reset him forward using my food delivery.

This is one of those tricky handling skills people struggle with. They can walk. And they can reach into their pocket to get a treat. But doing both at the same time is hard. It’s so like the expression about walking and chewing gum. This is clearly a skill that must be learned and practiced.

Here are some points to look out for: You don’t want to begin your food delivery before you click. That undermines the meaning of the click. And you don’t want to get the food out of your pocket and then put your feet into motion. That interrupts the flow of the pattern.

You want to click, then begin reaching into your pocket AS you turn to walk back to the front of his stall. You want this to become so automatic that you can do both together without thinking. That frees you up to focus on your horse’s response.

Dynamic Food Delivery

Now you could ask “why bother?” Why not just click, feed where you are and then ask your horse to step forward, click, then treat again? That accomplishes the same reset forward. It’s just broken down into more steps.

This certainly works, but it doesn’t gain you some extra bonuses. Most important, I want my horse to understand that sometimes he needs to move his feet to get to the treat. This active form of food delivery does many good things. It lets me reposition him so I can set him up for the next cycle of the behavior I’m focusing on.

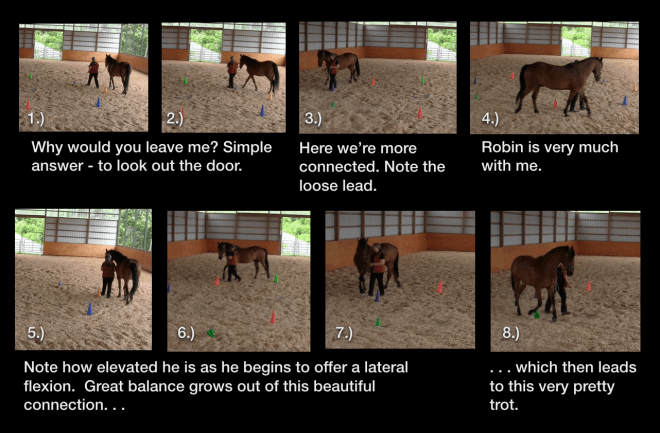

Earlier I described the “Why would you leave me?” game. This lesson provides us with a great example where moving to get the treat really helps both you and your horse learn the “dance steps” of the pattern. (https://theclickercenterblog.com/2016/07/27/) In this lesson you are walking your horse around a circle of cones. At some point you’re going to want to change direction. You can do this via the food delivery.

Food delivery gives you a sneaky way to execute a complex series of steps that some horses find quite challenging.

Mapping Out The Dance

It’s very much like trying to figure out the steps for a new dance. Once you’ve learned them, they seem effortless. How could you ever have struggled over something so easy? But right now you can’t figure out where to put which foot. What a mess. Arthur Murray where are you when we need you!?

That’s how your horse feels in the “Why would you leave me?” game. You’re asking him to stop, back up, swing his front end across, and walk off with you in the opposite direction. What a tangle! But if you make this dance sequence part of the food delivery, he won’t be thinking about which foot to put where. He’ll be following your lead before he’s even aware that he’s changed direction. You’re programing in the dance steps BEFORE you ask for them directly.

So it’s: click, you do your part of the dance as you reach for his treat. Next he does his part as he moves into position to take it from you. He’ll find it’s easy to stay with you. The dance is completed without his having to think about how he’s done it. You’re mapping this movement out in his nervous system. Once the map is in place, it will be that much easier to ask directly for the dance steps.

Using Food Delivery in the “Why would you leave me?” game to map out a change of direction.

You’re also getting a chance to watch how he moves BEFORE you ask directly for the steps. Does he back easily? Is he able to rock back into his hindquarters and step across into the new direction? No. Then he may have some arthritis in his hocks or some other condition that needs protecting. This kind of information makes a huge difference both in what you ask for and how you teach it.

Reading Your Dance Partner

The “why would you leave me?” lesson provides a great example of using dynamic food delivery. It’s such a useful strategy, but in clinics I often encounter horses who have only been fed in place. The first time I click and flow into my half of the dance, they don’t follow me. Just like everything else, this is a strategy that must be taught. I can’t expect my horse to understand that he needs to track my movement and move his feet to get his treat unless I have gone through a teaching process to explain this to him.

That’s a specific example of the basic training principle: you can’t ask for and expect to get on a consistent basis something you have not gone through a teaching process to teach to your horse. That and safety always comes first are twined together as the guiding principles that direct all my training. Following these two principles can help you avoid many training pitfalls and keep your training very positively oriented.

Normally, I teach the food delivery lesson early on. It’s part of his first introduction to targeting. (https://theclickercenterblog.com/2015/11/20/2015-clinic-season-an-introduction-to-clicker-training-day-1/) Once my horse figures out that he may need to track my movements to get to his treat, he’s going to pay even more attention to my body language. What hints or clues am I telegraphing that will let him know where he needs to be?

As he learns to step forward and back in response to the positioning of the treat, he’ll also be learning how to read me. When I rotate my shoulders towards him and extend my arm out towards the point of his shoulder, he’ll back up.

This lesson is introduced in the very first clicker lessons. I generally begin by having a horse touch a target. I’ll hold the target out in front of him. When he touches it, click, he gets a treat.

Robin has come forward to touch a target.

At first, I’ll make things easy for him. I want him to be successful, so I’ll deliver the treat about where the target was. He won’t have to move his feet to get to his treat. In the photo above this would keep his head on my side of the stall guard.

I would eventually like to be able to ask him to back up. If I’m working with a horse I don’t know, I won’t know what his past history with backing is. Has it been used as a punisher so he resents being asked to back? Does he have joint problems so backing is uncomfortable? I’d like to get a “read” on how he feels about backing, so I’ll introduce it first via the food delivery. As this lesson progresses, I’ll begin to step towards him so he has to back up to get his treat.

I’ve turned into Robin and extended my arm out towards the point of his shoulder. He backs up to get to his treat.

I think of the image of a swing door. If I swing the door (my torso) towards the horse, I am effectively closing the door, and he’ll back up. If I rotate in the opposite direction, I’m opening the door. I’m no longer blocking the space in front of him. Instead I’m opening that space to him and inviting him with the gesture of my leading hand to come forward.

Cues Evolve – Adding the Lead

Once my horse is consistently coming forward to touch a target and backing up to get his treat, I can clip a lead to his halter. Now I can combine the opening and closing of the “swing door” with cues from the lead. My horse will respond perfectly. I won’t need to escalate the pressure to “make” him back up. This is a very clear case of the cues evolving out of the shaping process.

Here’s the summary of this lesson:

Beginning with some of his very first clicker training lessons, my horse learned to back up or come forward to get his treats. That was easy. In the process he became aware of the clues my body orientation was giving him so he could get to the treats more efficiently. If the treats are going to be presented forward, there’s no point in getting ready to back up. You need to read your human to know which one it’s going to be.

These hints can then be transferred to a different part of the movement cycle. The hints are no longer part of the food delivery. Now they are the main event. They come before the click. I’ll use them to ask for the behavior I want. This process lets me use the food delivery to help my horse learn how to respond to the lead.

By tracing these reaction patterns back through a series of lessons, you can see how your horse’s ability to read your body language cues has been evolving beginning with the very first clicker lesson. You have been building the components you’ll need one small step at a time for the more complex lessons that are to come.

This points up how important the foundation lessons are. Ideally, no matter how complex a lesson may seem to an outside observer, for my horse the correct answer should be only one small, very attainable step away. If I jump into the middle of a teaching progression, that won’t be the case at all. I won’t have the underlying components in place. I’ll be teaching my horse three or four new things all at once, and I’m likely to end up in a muddle.

In the backing in a square exercise I’ll want him to back up and then come forward to get his treat. If he’s never moved his feet to get to his treat, he won’t understand what has just happened. I clicked, but then I marched off before he could get his treat. It will feel like a broken click, a broken promise, and he may shut down on me. But, if in an earlier lesson I have taught him to walk forward to get his treat, this component will be well understood. He’ll follow me forward to get his treat, so we’ll be set up to repeat the movement cycle. I’m only introducing one new element at a time, not three or four. In this case my horse already knows how to back up when asked, and to come forward after the click to get his treat. The new element is he’s backing within a confined space.

The key to good training is this progressive, step-by-step building of components. Lessons are only complex when they are not well prepared. Build the underlying layers well, and you can turn the difficult into the achievable.

This is one way in which cues evolve out of the shaping process. Here’s another.

Cues Evolve: How Light Can Light Be?

Now that I have my horse backing easily when I rotate toward him as I slide down the lead, I’ll begin to notice that he is already backing before I can get very far down the lead. Great! My cues are getting lighter. I’ve now opened up a whole new game to play. The goal is to see how little I need to do to get a correct response from my horse. How little do I need to do to get him to back? How far do I need to rotate? Look, I just move my shoulder slightly and he’s already backing. Click! Give him a treat with some laughter added on top.

Horses are superb masters at this game. They have to be given the herds they live in. To keep from running into one another they need to be able to read and predict movement.

When Robin and I were sorting out one of the many leading patterns I’ve wrestled with, I’m sure he thought me the rudest, clumsiest dance partner ever! I was forever in his space, “stepping on his toes”. How annoying! When I finally figured out how to ask for the sequence I wanted without crowding into him, you could see from his expression the immense relief he felt. Finally, he was getting somewhere teaching his very awkward pupil!

Who’s Not Showing Respect?

People are forever talking about respect – by which they usually mean the horse needs to mind his manners and stay out of their way. But really this goes both ways. We’re often the clumsy ones not understanding how to give our much larger dance partner the space he needs to maneuver.

Here’s something else to consider: when a horse is startled, he will often crowd in on top of us. We humans often view this as very rude, disrespectful behavior. But look at it from the horse’s point of view. What should he be doing when his herd is threatened? Bunch in closer together to make it harder for a predator to get at any one of them. He isn’t being disrespectful at all. He’s trying to keep you both alive! But that very generous act can get a human seriously hurt. That’s why we are teaching him some alternatives to crowding on top of us.

The food delivery has tuned you both into body language. He now tracks you beautifully, and you’ve been able to transfer your cues to the front end of the process, ahead of the click. You started out with a big obvious rotation of your body, but that’s now evolved into a whisper. Tighten a shoulder muscle, and he rotates back. What fun!

Now that he’s tuning into you, you’ll begin to notice even more ways in which your body language is giving him clues about what you want. Before you can give your big deliberate cue, he’s already read what you want and responded to you. You’ll need to decide if you want him to be this light, or do you want him to wait for a signal you’ve chosen.

This is often what people mean when they talk about attaching a cue to a behavior. But as you can see the cues are already there. It’s more a matter of deciding which of these signals are you going to highlight and make more definite.

You get to decide if you are going to make deliberate use of the small cues your horse is already using. You can only do that if you understand the process so you can be on the lookout for these subtle cues. Otherwise, if you block him when he starts to respond to these signals, you could end up confusing him.

One of the training mantras I repeat often in clinics is: don’t make your horse wrong for something you’ve taught him.

Being aware of the way in which cues evolve out of the shaping process is one of the ways you can help your horse to be right.

Coming Next: Starter Button and Constant-On Cues

Author’s note: Once again, I want to remind people that I am using these lessons to illustrate some important concepts. These articles are not intended to give detailed, how-to instructions. For those resources refer to my web sites, and to my books, DVDs, and on-line course. In particular refer to my book, “The Click That Teaches: A Step-By-Step Guide in Pictures”, and the early DVDs in the DVD lesson series: Lesson 1: Getting Started with the Clicker, Lesson 2: Ground Manners, and Lesson 3: Head Lowering. My on-line course will also provide you with very thorough how-to instructions.

Remember, if you are new to the JOY Full Horse blog, click on the JOY Full Horses tab at the top of this page to find the full table of contents and links to each of the articles I have published so far.

I hope you will want to share these articles by sending links to this blog to your friends. But please remember this is copyrighted material. All rights are reserved. Please do not copy any of the “JOY Full Horses” articles without first getting written permission from Alexandra Kurland, via theclickercenter.com

Also note: these articles are not intended as an instruction guide for introducing your horse to clicker training. If you are new to clicker training and you are looking for how-to instructions, you will find what you need at my web sites:

theclickercenter.com theclickercentercourse.com