2018 marks the twentieth anniversary of the publication of “Clicker Training for your Horse”. I am celebrating by writing thank yous each month to people who helped bring clicker training into the horse world.

Are you trying to guess who it’s going to be this month? Anyone who has followed my work knows the stories. You’ve met the horses through my books and DVDs. Who will I single out this time?

I could turn it into a guessing game. This person has appeared in the game show: “What’s my line?”. Does that help? Maybe not. But if I tell you that the panelists correctly guessed that she was a dolphin trainer, now some of you will know who I’m talking about. July’s tribute belongs to Karen Pryor.

So many of us were first introduced to clicker training through Karen’s book, “Don’t Shoot the Dog”. I discovered her book through a friend who bred and trained Irish wolf hounds. We were having lunch together (with one of her wolf hounds literally looking over my shoulder). Needless to say, we were talking about training. I’ve forgotten the exact subject, but I do remember my friend saying, “But of course, you’ve read “Don’t Shoot the Dog”.

She said it in a tone that implied that of course I had. How could I not? But in 1993 I had never even heard of “Don’t Shoot the Dog”. Perhaps if Karen’s publishers had called it “Don’t Shoot the Horse”, the horse world would have been exploring clicker training ahead of the dog world. We’ll never know. But in any event, I tracked down a copy of “Don’t Shoot the Dog” and read it with great interest.

Those of you are familiar with Karen’s book know that it is not a training book per se. Karen was writing about learning theory, a subject which can sound very dry and off-putting. “Don’t Shoot the Dog” is anything but. You read it, nodding your head in agreement. “That’s why that horse, that dog, that person responded in that way. It all makes so much sense! How could they do anything else.”

When I read the chapter on punishment, I remember thinking, “The horse world needs to know about this.” The horse world needs to understand that when you use punishment, there is ALWAYS fallout. You always get other unintended, unwanted consequences. Punishment doesn’t work with laser-fine precision. You may shut down the behavior you’re after, but the effect spreads out and creates negative consequences and a general dampening down of behavior.

Use it often, and you will get what in the horse world is often called a “well behaved” horse, meaning a shut down horse. Punishment stops behavior. That’s the definition of punishment (versus reinforcement). When you use reinforcement (plus or minus), the behavior you’re focusing on increases.

When you use punishment, the behavior decreases. So you may punish biting. Strike hard enough, fast enough, the biting may indeed stop – for the moment. But punishment isn’t a teaching tool. It doesn’t tell the horse what TO DO to avoid the unwanted consequence. However, it is reinforcing for the punisher. That’s what makes it such a slippery slope. It may not get the results that you’re after, but in the moment, oh it can feel so good.

When skilled positive reinforcement trainers talk about the four quadrants meaning positive and negative reinforcement, and positive and negative punishment, they don’t take the use of punishment completely off the table. They recognize that under the right conditions punishment – applied well – may be a necessary and correct choice.

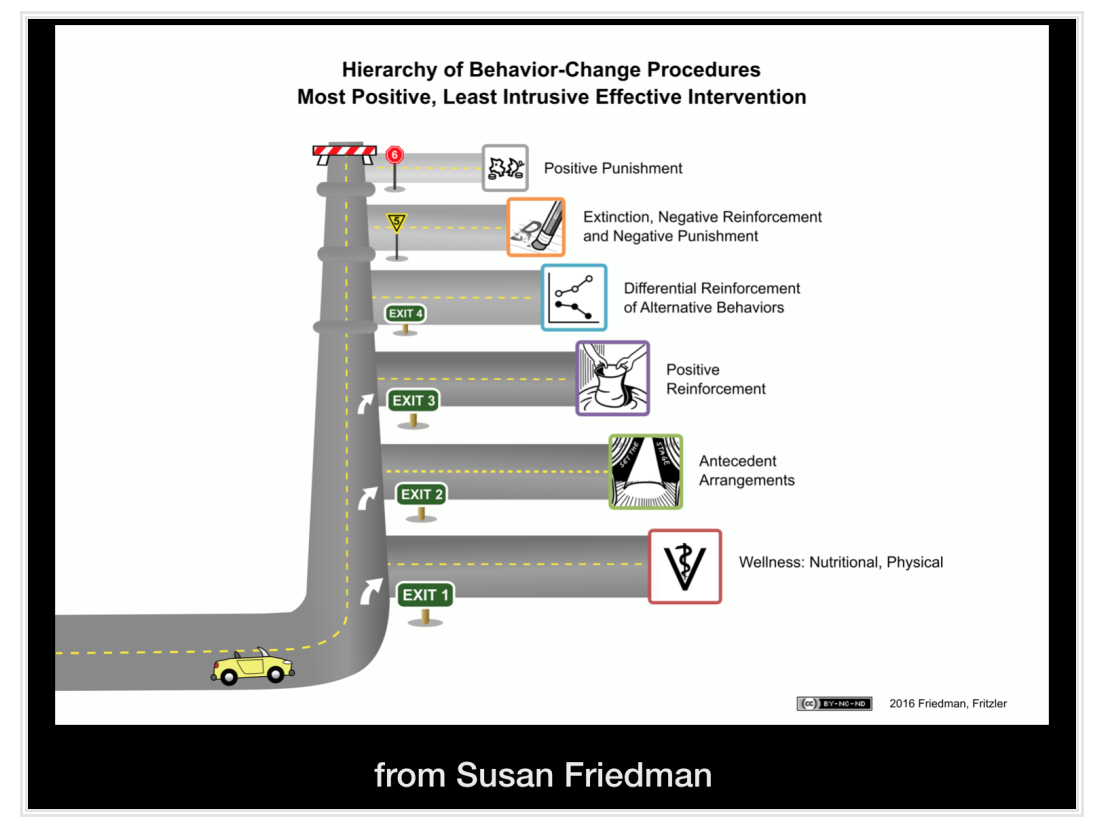

In many of her presentations Dr. Susan Friedman talks about the hierarchy of behavior-change procedures.

You begin with the least intrusive interventions. You begin by exploring medical reasons for the behavior, then you move to changing the environment, and positive reinforcement procedures. Only after many steps and pausing always to consider if there might be other alternatives, would you consider the more intrusive methods and sitting last as a possibility would be punishment. And before people puff themselves up and say – I would never use punishment, remember Dr Friedman spent much of her career working with children with major behavioral problems that included self-injurious behavior. So what would you do with a child who is trying to gouge her eyes out? Is punishment of that behavior always off the table?

Punishment is certainly not where you begin, but there may be extreme situations where it is where you end up. If a fire were fast approaching, and you needed to load a reluctant horse on a trailer NOW or leave him behind, would you resort to punishment? Until you’re faced with that situation, it’s an open question.

Ken Ramirez, another trainer I greatly admire, doesn’t take punishment off the table either. However, when he was overseeing the training program at the Shedd Aquarium, the novice trainers were only allowed to use positive reinforcement. They could reinforce behaviors that they liked, but they had to be non-reactive to behaviors they didn’t like. Only when they were more skilled could they begin to use more advanced techniques. In his talks on this subject Ken explains why he puts these limits on his young trainers. At some point early in their career they will come to him, asking for permission to move up the hierarchy.

“Ken,” they will say, “I could so easily solve this problem we’re having with this animal if only you would let me use this procedure that I’ve read about.” Ken won’t let them. He wants them to become very experienced with the basics. If you let them begin to add in other techniques too soon, they really never learn how to be skilled and creative with the basic tools. They jump the queue too fast and head for more intrusive techniques.

As they become more skilled, he lets them expand into the rest of the hierarchy. His senior trainers can use any technique, including punishment, that they deem to be appropriate. But he knows that these trainers have the experience and the skill to apply punishment well, meaning with good timing and at the right intensity to create the desired effect and minimize the fallout. He also knows that they are so skilled and experienced that they don’t need to use punishment. They will find other alternatives.

The odd thing in the horse world is we flip things upside down. We reach first for punishment. The horse bites – we strike. It’s the horse’s fault. And if he bites again, we’ll hit him harder. We don’t look first for medical conditions. Maybe that horse is full of ulcers. Treat the ulcers and his reason for biting will go away. We don’t rearrange the environment. Use protective contact – put a barrier between you and the horse so he can’t bite you, and then use positive reinforcement to teach him alternatives to biting.

Instead we give six year old children riding crops (often pink riding crops with pretty sparkles), and we tell her to hit her pony harder. We give punishment to the least experienced, most novice riders. That’s completely upside down. No wonder what we get back are so many sad stories, so many bad endings for both people and horses.

When I said the horse world needs to understand what Karen was saying about punishment in “Don’t Shoot The Dog”, I’ve always though some genie of the universe heard that. “Got one! She’ll do.” I was sent the clicker training bug. More than that, that genie sat on my shoulder and kept urging me to write about what I was experiencing with my horses. Lots of people, including Karen Pryor, had used clicker training with their horses before I ever went out to the barn with clicker in hand. I was by no means the first person who ever used it with a horse. But they didn’t disappear into their computers to write about it. That good genie on my shoulder made sure that I did.

“Don’t Shoot the Dog” sparked my interest. I wanted to know more about clicker training. I read “Lads Before The Wind”, Karen’s chronicle of the founding of Sea Life Park and the development of the first dolphin shows. She shared with us the many training puzzles that had to be solved in order to figure out how to train dolphins. Old-style circus training wasn’t the answer. She turned to science and the work that was coming out of B.F. Skinner’s lab.

“Lads Before The Wind” took me a step closer. I wanted to know more about training with a marker signal.

My friend brought me a copy of a magazine article she thought I’d find interesting. I have no idea what the article was about. I’m not even sure that I read it, but down in the left hand corner, in very small print, was a tiny ad for two of Karen Pryor’s early VHS videos. I sent away for both.

The first one was recorded at a seminar that Karen gave with Gary Wilkes to a group of dog trainers. Gary was the canine trainer who approached Karen with the question: “Do you think clicker training would work with dogs?”

In a conversation I had years ago with Karen, she said she had always had dogs, but they weren’t really trained, not like she had trained the dolphins. They were just around. But when Gary wondered if clicker training would work with them, Karen thought, of course! Why not! So she and Gary teamed up to give a series of seminars to dog trainers, and we all know what grew out of that for the dog world.

The clip from that seminar that intrigued me and sent me out to the barn to try clicker training my horse showed Gary training a twelve week old mastiff puppy to sit and then to lie down – all without touching the puppy. These days that’s become so the norm, it wouldn’t get a second look, but in 1993 the dog training I had seen involved leash pops and pushing on the puppy to make it sit. I was intrigued by the ease with which Gary got this puppy to lie down and stay down.

I was even more intrigued by a clip that was on the second video. It featured Gary Priest, the Director of Training at the San Diego Zoo. Gary talking about an African bull elephant named Chico. Chico had tried to attack his keepers on several occasions so the decision had been made that no one could go into his enclosure with him. So for ten years Chico had gone without foot care. At that time the farrier literally got underneath the elephant to trim the front feet. Gary showed a video of a farrier standing under the elephants belly to trim a foot. “One wrong move from the elephant,” Gary says in the background – point taken.

So they had to come up with a different approach for Chico. Gary decided to try clicker training. They built several small openings in the gate to Chico’s enclosure. Then they used targeting to bring him up to the enclosure gate. It took many months, but they finally taught him to put his foot through the opening and to rest it on a metal stirrup bar for cleaning.

The video showed the keepers using targeting to guide Chico to turn around so his hindquarters were to the gate. Then following a smaller target, Chico lifted his hind foot through the opening for his first trim in ten years.

Gary says in the voice over: “I can’t impress upon you enough how aggressive this elephant was, but he’s standing here quietly all for the social attention and the bucket of food treats.”

I know how all too many horses even today get handled when they refuse to pick up their feet. With some trainers, sadly, out come the lip chains, the hobbles, and three men and a boy to hold the horse down, all to force compliance. We in the horse world do indeed have a lot to learn.

Those two videos gave me what I needed to get started. I’ve told this part of the story many times. My thoroughbred, Peregrine, was laid up with hoof abscesses in both front feet. I wanted to keep him mentally engaged during what was likely to be a long recovery. What a perfect time to give clicker training a try. I went out to the barn with treats and a clicker.

In “Lads Before the Wind” Karen had talked about charging the clicker. With the dolphins you blew a whistle then tossed a fish, blew a whistle then tossed a fish – until you saw the dolphins begin to look for the fish when they heard the whistle. Now you could begin to make the blowing of the whistle contingent on a specific behavior. For example, now the dolphin has to swim in the direction of a hoop suspended in the water. Swim towards the hoop, and wonders of wonders, you can make the humans blow the whistle and throw you a fish. That’s a powerful discovery. Suddenly the animal feels in control.

I tried charging the clicker. I clicked and treated, clicked and treated. Peregrine showed no signs that he was connecting the click to the treat. I remember thinking: “If this is going to take a long time, I’m not interested.”

I decided to try targeting. There was an old dressage whip propped against the corner of the barn. That would do. I held it out. Peregrine sniffed it. Click, treat. I held it out again, same thing. The ball was rolling.

I couldn’t do much more than ask him to target. His feet hurt too much to take more than a step or two, but as he began to recover, I could ask for more. I started to reshape all the things I had taught him over the years, everything from basic husbandry skills to the classical work in-hand I was learning. When I started riding him seven weeks later, he was further along in his training than he had been before he was laid up.

Hmm. Long lay-ups aren’t supposed to work that way, especially not with a thoroughbred. Normally, as they recover, you go through a rough patch where they’re feeling very cooped up and your job is to convince them to walk not rear during hand walking. With Peregrine there was no rough patch. And he was understanding what I was asking of him so much better that he did before the lay-up.

The good genie that sat on my shoulder had picked well. It was no accident that clicker training gained such a strong toe hold with me. I’ve known so many people who gave clicker training a try, loved their horse’s response to the initial targeting, and then got stuck. What do you do with it? For them ground work meant lunging – and often lunging badly. Ugh. We just want to ride!

I wanted to ride as well, but I also loved ground work. I had raised all my horses, so ground work to me meant so much more than lunging. It meant teaching a young horse all the skills it would need to get along with people. It meant learning how to stand quietly for haltering, grooming, foot care, medical procedures, saddling, etc.. It meant learning to lead and from that core foundation, learning about balance through the classical work in-hand and all the performance doors that opened up. It meant expanding their world by introducing distractions and new environments. The list went on and on. And finally it meant connecting the ground work into riding. Riding truly is just ground work where you get to sit down.

So as Peregrine began to recover from his abscesses, I had a lot to play with. My training was already structured around systematic small steps. It was easy to add in the click and a treat. At first, you could say that all I was doing was just sugar coating same-old same old. I would ask in the way I knew and then click and treat correct responses. But even just that first step into clicker training was producing great results. And when I explored targeting and free shaping – WOW! – was that ever fun!

I was liking this clicker training! So I began to share it with my clients. Together we figured out how to apply it to horses. So fast forward three years to July of 1996. I had written a series of articles that I wanted to put up on the internet. I had built a web site, but I wasn’t sure if I could use the term clicker training. Gary Wilkes had trademarked “Click and Treat” and the llama trainer, Jim Logan, had trademarked “Click and Reward”. It was frustrating. If people kept trademarking all these phrases, pretty soon there would be no way to refer to the training.

So I emailed Karen. I introduced myself and sent her the articles I wanted to publish on my web site. I needed to know if she had trademarked clicker training. Could I use the term in my articles?

Twenty-four hours later I received an email back from Karen. She had read my articles. Would I like to write a book about clicker training horses for her publishing company?

You know the answer. Karen gave the “ball” a huge push down the hill. So thank you Karen. Thank you for that initial support. For me personally it was a great pleasure working with you on the editing of that book. And over the past twenty years I have treasured our continued friendship.

At one of the early Clicker Expos when you were introducing the faculty, when you got to me, you began by talking about conventional horse training. You described it as what it is – organized horse abuse. Wow. To be brave enough, bold enough to say it out loud. It was shocking to hear, but so true. You understood the horse world. You knew about the wide-spread use of punishment. You knew the importance of bringing positive reinforcement into this community.

You couldn’t be everywhere, doing everything yourself, but when you asked if I wanted to write a book, you gave the clicker training ball a huge push. Twenty years later, the book we created together is still helping horse people to find alternatives. And the horse world is changing!

Thank you Karen.

I have a new book coming. It will be published April 26, on the anniversary of Peregrine’s birthday. You’ll be able to pre-order it soon. I’m still getting all of that set up. I’ll have more details about how you can order the book coming soon.

I have a new book coming. It will be published April 26, on the anniversary of Peregrine’s birthday. You’ll be able to pre-order it soon. I’m still getting all of that set up. I’ll have more details about how you can order the book coming soon.

On the third day Ken focused on husbandry, especially as it relates to medical care. He is uniquely qualified to speak on this subject. Both at the Shedd and through his consulting work, he has overseen the teaching of cooperative husbandry procedures not just to more animals than most of us will ever handle in a lifetime, but to more species as well.

On the third day Ken focused on husbandry, especially as it relates to medical care. He is uniquely qualified to speak on this subject. Both at the Shedd and through his consulting work, he has overseen the teaching of cooperative husbandry procedures not just to more animals than most of us will ever handle in a lifetime, but to more species as well.