In Search of Excellence

In March we celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the Clicker Expo. The theme for the Expo was centered around excellence. The Expo organizers wanted the presenters to talk about what made their work consistently stand out – what accounted for our success in training and teaching. This was originally supposed to be the theme of the 2020 Clicker Expo, but then the pandemic got in the way, so we had a lot of time to think about this topic.

Yesterday I wrote about Peregrine’s mother. She had neurological damage which meant, especially early on, she would frequently lose her balance and fall. I was told by my vet that there was no treatment for her, and in all likelihood her condition would worsen and I would be forced to put her down. The risk of her falling on someone would mean she would simply become unsafe to handle.

I saw her fall. I knew the risks and I chose to work with her anyway. How could I not? I loved her.

When I was around her, I was always careful. And I was always afraid in a way that I had not been before when I was around horses. My fear shaped my training choices.

So when I thought about this question for my Expo presentation: in general what are the procedures, the techniques, the principles that help people to excel in their training, I came up with what might seem to many to be an unexpected answer.

But before I give you my answer, I first want to ask what is excellence anyway? What does it mean to you?

The dictionary defines it as: “the quality of being outstanding or extremely good.”

That’s a nice feeling to think that we are outstanding in something. And we are. Every one of us is an expert. We are an expert in our own life experience. Nobody knows more about your life than you do.

So when I was thinking about this question of excellence, I was thinking about what for me is the difference that has made a difference?

Here’s my answer: what helped me to be a better trainer comes down to one word and that’s fear.

This is an interesting answer because, of course, I am a positive-reinforcement trainer. I want my learners to be moving towards activities that they enjoy, not away from aversives. I work hard to set up positive-reinforcement scenarios for both the horses and the people I work with. But scratch below the surface of my training and what motivates my search for training excellence is fear.

There are two kinds of fear. There’s the fear of something. Horses are big. That’s such an obvious statement it almost seems silly to point it out. But I think this is one of the reasons that horses make us look more deeply below the surface of our training choices than working with dogs typically does.

Dogs can certainly be dangerous. They are predators, after all, but for the most part they are harmless family pets. They jump up on people and lick their faces. They run around their feet and bump into them. They pull on leashes and for the most part people manage to stay upright. The same behavior in a horse could land you in the hospital. Horses are bigger than we are. They are stronger than we are. They are faster than we are. When they are excited or afraid, they can very definitely hurt us. Plus we get on their backs! We compound the risks by riding them, so fear of being hurt represents a rational response to being around a large, potentially volatile animal.

Then there’s the fear for something. Dog owners know this kind of fear. It very definitely can effect their training choices. Think about this situation: You don’t want your dog running out the front door because he could end up in the road and be hit by a car.

That fear motivates many people to adopt punishment-based solutions. They aren’t cruel, mean owners. They love their dogs. They don’t want to lose them. That’s the motivation that sits behind choosing training methods that cause fear or pain. They want to stop the behavior of running out the front door to prevent something much more horrible from happening. Interesting. Give them a kinder solution and they’ll switch – provided it’s effective. If we want to move owners away from punishment-based solutions, education matters.

Size Matters

Horses are big. And as strong as they are, they are also very fragile, so horses confront us with both kinds of fear, and often at the same time. Training minis revealed to me how much size effects our training choices. Panda, the mini I trained to be a working guide for her blind owner, came to me when she was nine months old. The first day she was with me I brought her into my house. It was such a novelty. There’s a horse in my house! She was so small I wasn’t worried at all. She was the size of a large dog. She weighed only a hundred pounds. In horse terms she was 7.5 hands tall (28 inches at the withers). If she had gotten under a table or trapped somehow in a tight space, I could easily have helped her out. But when a full sized horse gets cast in a stall or trapped under a fence, you may need four or five strong people to get the horse untangled. Size makes a difference. If you have only trained big horses, I very much recommend that you find a mini-sized mini to work with. Panda revealed how much size makes a difference. For me I know it certainly colors the risks I am willing to take and the training decisions I make.

Size matters in others ways. When I took Panda for walks in those early days, she used to stand up on her hind legs like a goat. She was amazingly well balanced. When she reared up, I just laughed. She was so tiny. She was only 28 inches at the withers. So when she reared up, it was cute. If she had been a nine month old warmblood, I probably wouldn’t have been laughing. Size matters. Training minis is a useful exercise. It really does reveal how much our training is colored by the size of the animal we work with.

My horses have free run of the barn, that includes the barn aisle and other spaces that horses don’t typically have free access to. I am very comfortable with them. I couldn’t give them this life style if I wasn’t very confident that they are safe to be around, even in tight spaces. But even so I respect their size. I am mindful of how I move around them so we all remain safe. Fear isn’t on the surface. I know my horses are mindful of me, as well. They have shown me that they will actively avoid bumping into me, but mistakes can happen. So fear sits in the background and influences how I evaluate the safety moment to moment of every horse-human interaction.

In the horse world fear is everywhere. It’s easy to spot. All you have to do is look for tension. You’ll see it in the horses. And you’ll see it in the riders, even riders at very high levels. Look for the tension in their arms, the tightness in their bodies, the hold on the reins. Only we don’t call this fear. We call it being tough, being assertive. Being afraid in the horse world isn’t acceptable. Riders who are afraid are shamed. Horses who are afraid are punished.

Another place you can see how afraid riders are of their horses is at tack stores. Look at all the leverage devices that are used to control horses. Why do we need to control them? Because we are afraid of them. Only that fear is hushed up, glossed over, called something else.

The Legacy of “Get Back On Your Horse” Training Attitudes

In the horse world when you take a tumble, it is get back on your horse. You aren’t allowed to be afraid. Unless you are so hurt you are being airlifted off to a hospital, it is get back on. Conquer your fear and conquer that horse. We have inherited this attitude from the age in which horses were used for transportation. The phrase “get back on your horse” has become part of normal speech. If you have a disaster at work, you are instructed to get right back out there. People who have never been near a horse in their entire life are told: “You have to get back on your horse.”

In a previous post I wrote about my experience at a hunter jumper barn. There I saw attitudes that are all too common in the horse world. In lessons people were told to get over their fear.

They were told to push past it, “to get back on their horse”. If a horse refused a fence, he was just being lazy. He was testing you. He was stubborn.

The solution that was offered was to get after him and make him do it. Get tough. Go straight at the brick wall and go over it. Being afraid wasn’t an option.

The horse world has no patience for those who can’t. You have to be brave and make the horse do it.

So I went to the dictionary again to find out what brave means. The horse world agrees with the dictionary definition: brave – adjective: ready to face and endure danger or pain; showing courage.

Next I went to the thesaurus. That was interesting. The synonyms the thesaurus gave me made me feel as though I was in the swashbuckling era of the early Hollywood movies. They evoked images of the three musketeers or old John Wayne movies.

Brave is synonymous with: courageous, plucky, fearless, valiant, valorous, intrepid, heroic, lionhearted, manful, macho, bold, daring, daredevil, adventurous, audacious, death-or-glory; undaunted, unflinching, unshrinking, unafraid, dauntless, indomitable, doughty, mettlesome, venturesome, stouthearted, stout, spirited, gallant, stalwart.

Interesting. These were certainly words that were valued in “brick-wall” training. But my horse was showing me these weren’t qualities that helped her. And they certainly didn’t describe me.

Finding Alternatives

So what is the alternative to being brave? I was just beginning to learn about training. Compared to the people around me I had very limited skills. But I had two things going for me that they either ignored or steam rolled over because they could.

I was patient.

And I was persistent.

Plus I loved my horse. I wanted to put off for as long as possible the day her neurological impairments would force the decision to have her put down.

So you can definitely say that FEAR sits at the center of what drove me to become a better trainer.

Instead of pushing FEAR aside, instead of trying to pretend it wasn’t there, or feeling as though I wasn’t good enough because I felt afraid, I turned things around and learned to listen to that fear.

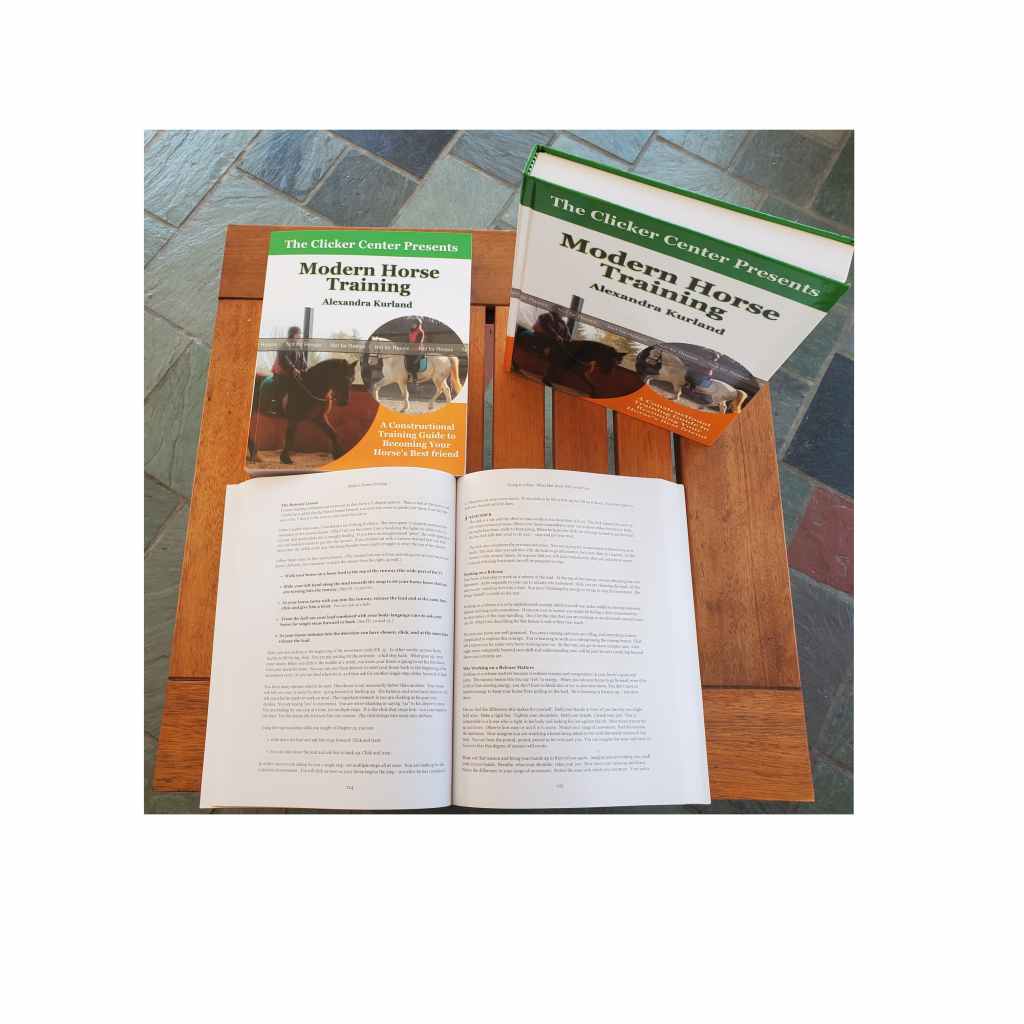

I was afraid of my horse and for my horse, both at the same time. Instead of running from fear, I listened to it. I used it. It shaped my training in a good way. I found solutions that were horse friendly, that sidestepped fighting with horses and instead helped me to become what the subtitle of my new book celebrates – my horse’s best friend. The new book, “Modern Horse Training: A Constructional Guide To Becoming Your Horse’s Best Friend” is very much a product of the forty year journey my horses have sent me on.

I know from teaching thousands of people that I am not alone in feeling afraid of my horses and for my horses. And I also know that many of these individuals have encountered the same message that I observed in that hunter jumper barn: Get over your fear. Get tougher. Get back on your horse and show him who is the boss.

I have taught people who now struggle to ride because they listened to someone else instead of to their own fear. When they got back on, their horse sent them flying. Broken bones were the result. The brick wall that is their fear now looms so high it can’t be ignored. There are still ways around the wall, but it’s a longer journey than it needed to be.

This isn’t universal. You may have been lucky enough to start out in a barn that taught through compassionate, learner-centric methods such as Sally Swift’s Centered Riding or some other equally kind form of instruction. But the old attitude sadly is still there in far too many barns. It is so embedded in the training world, you may not even be aware of it. It is just the norm, the way things are done. If you’re an instructor, of course you find yourself telling a student to get back on after a fall. It’s what you were told. It’s what you did.

But it’s not what our horses are asking for, and it’s certainly not a match with the kind of relationship that many of us are looking for when we get a horse. We want to ride, and, yes, absolutely we want adventures. But we want them want them with our best friend, not a sparing partner.

The title of the new book, “Modern Horse Training”, refers to this shift in thinking. The older forms of thinking used punishment to suppress fear. There is an alternative.

“Modern Horse Training” offers another way forward. I’ll show you what emerges when instead of trying to suppress the fear, you acknowledge it, you listen to it – both in yourself and in your horses. It lets you develop teaching strategies that build confident, eager, resilient, enthusiastic learners. There’s no pushing through brick walls. Instead there is good instruction built around the much kinder path of constructional training and positive-reinforcement procedures.

The new book will be published on April 26, 2023. You will be able to order it through my web site: theclickercenter.com and also through Amazon and other booksellers. It will be available in hardcover, paperback and as an ebook.

In the coming posts I’ll share with you some of the many good things that have evolved in my training because I learned to listen to that little voice inside me that was telling me to be careful. Coming next: Everything is Connected to Everything Else

Here’s another example: Your horse doesn’t want anything to do with the shiny new trailer you’ve just bought for him. You picked it out especially with his comfort in mind. It’s an inviting space with lots of windows, and a bright interior. He’s always been good going up over platforms and onto the wooden bridges you’ve built for him. But now he’s got his feet planted at the foot of the trailer ramp, and he’s refusing to go another inch forward. Anytime you’ve gotten him to move, it’s been over the top of you trying to get back to his pasture mates.

Here’s another example: Your horse doesn’t want anything to do with the shiny new trailer you’ve just bought for him. You picked it out especially with his comfort in mind. It’s an inviting space with lots of windows, and a bright interior. He’s always been good going up over platforms and onto the wooden bridges you’ve built for him. But now he’s got his feet planted at the foot of the trailer ramp, and he’s refusing to go another inch forward. Anytime you’ve gotten him to move, it’s been over the top of you trying to get back to his pasture mates.